I publish an "Editorial and Opinion Blog", Editorial and Opinion. My News Blog is @ News . I have a Jazz Blog @ Jazz and a Technology Blog @ Technology. My domain is Armwood.Com @ Armwood.Com.

What To Do When You're Stopped By Police - The ACLU & Elon James White

Know Anyone Who Thinks Racial Profiling Is Exaggerated? Watch This, And Tell Me When Your Jaw Drops.

This video clearly demonstrates how racist America is as a country and how far we have to go to become a country that is civilized and actually values equal justice. We must not rest until this goal is achieved. I do not want my great grandchildren to live in a country like we have today. I wish for them to live in a country where differences of race and culture are not ignored but valued as a part of what makes America great.

Saturday, September 29, 2018

Jeff Flake Says He Was Moved By 'Emboldened' Women, Drive To Make Process 'Fair' | HuffPost

"Arizona Republican Sen. Jeff Flake’s surprise call Friday for a delay in the final vote on Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation was affected by encounters with women “emboldened” to share their experiences and his desire to demonstrate that the “process is fair,” he told reporters Friday.

He said it was “remarkable” how many people who “saw Dr. [Christine Blasey] Ford [testify] were emboldened to come out and say what had happened to them,” Flake told reporters. “I heard from friends, close friends. I had no idea.”

Flake referred to his “interactions with a lot of people — on the phone, email, text, walking around the Capitol, you name it.”

Earlier in the day, Flake had issued a statement saying that he wasn’t convinced Blasey’s testimony accusing Kavanaugh of sexual assault was enough to deny the Supreme Court nominee a vote.

A short time later, Flake was confronted as he entered an elevator by two survivors of sexual assault who challenged him on Kavanaugh in an encounter captured on video that went viral. “What you are doing is allowing someone who actually violated a woman to sit on the Supreme Court. This is not tolerable,” one of the women shouted.

Flake, who left the elevator ashen-faced and clearly rattled, did not reveal to reporters if that encounter affected his ultimate decision to call for a one-week delay in a final vote on Kavanaugh’s confirmation to allow time for an FBI probe. But he had already been talking the night before with Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine), Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) and Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia about how to deal with the Kavanaugh accusations without rejecting his confirmation outright, sources told Politico. Together they would hold the power to block Kavanaugh’s final confirmation on the Senate floor.

Flake told reporters that his morning statement was a bid to keep Republicans calm about where he stood and not worry that he was going to bolt from their ranks. “I hoped that would help provide leverage,” Flake said.

But he was also determined to demonstrate “that the process is fair, even if Democrats are “not going to vote for” Kavanaugh, Politico reported.

Flake reached out Friday to Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.), who’s a fellow member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, and discussions began. After joining Republicans on a party-line vote to advance Kavanaugh’s nomination out of the committee, Flake then called for an FBI investigation into the accusations against Kavanaugh before a final Senate vote. He made clear that he wanted a probe of “not more” than a week.

“This country is being ripped apart here, and we’ve got to make sure we do due diligence,” he told the committee.

“I wanted to support” Kavanaugh, Flake told reporters later. “I’m a conservative, he’s a conservative judge. But I want a process we can be proud of, and I think the county needs to be behind it.”

Jeff Flake Says He Was Moved By 'Emboldened' Women, Drive To Make Process 'Fair' | HuffPost

Friday, September 28, 2018

Women confront Flake on Kavanaugh support. John Armwood This video and Senator Flakes's reversal show the naive of those who constantly call for civility by political activists. These people lack the real world experience that has always demonstrated that confrontation is a necessary prerequisite for fruitful negotiations. We had a discussion here on Facebook a few months ago when Trump administration officials were confronted at dinner. They were wrong then. I hope they learn something from this example. This video and Senator Flakes's reversal show the naive of those who constantly call for civility by political activists. These people lack the real world experience that has always demonstrated that confrontation is a necessary prerequisite for fruitful negotiations. We had a discussion here on Facebook a few months ago when Trump administration officials were confronted at dinner. They were wrong then. I hope they learn something from this example.

Brett Kavanaugh: American Bar Association calls for FBI investigation

"The American Bar Association has asked the Senate Judiciary Committee to suspend its consideration of Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court until an FBI investigation is completed into multiple sexual assault allegations..."

Brett Kavanaugh: American Bar Association calls for FBI investigation

The Ford-Kavanaugh Hearings Will Be Remembered As a Grotesque Display of Patriarchal Resentment | The New Yorker

"Judge Brett Kavanaugh is almost certainly going to be appointed the next member of the Supreme Court of the United States. Whatever Christine Blasey Ford said in her testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Thursday, and whatever Kavanaugh said in his, and however credible and convincing either one seemed, none of it was going to affect this virtual inevitability. The Republicans, if they stick together, have the necessary votes. A veneer of civility made it seem as if the senators were questioning Ford and Kavanaugh to get to the truth of whether Kavanaugh, as a drunk teen-ager, attended a party where he pinned Ford to a bed and sexually assaulted her, thirty-six years ago. But that’s not what the hearing was designed to explore. At the time of this writing, composed in the eighth hour of the grotesque historic activity happening in the Capitol Hill chamber, it should be as plain as day that what we witnessed was the patriarchy testing how far its politics of resentment can go. And there is no limit.

Dressed in a blue suit, taking the oath with nervous solemnity, Ford gave us a bristling sense of déjà vu. “Why suffer through the annihilation if it’s not going to matter?” Ford had told the Washington Post when she first went public with her allegations. With the word “annihilation” she conjured the spectre of Anita Hill, who, in her testimony against Clarence Thomas, in 1991, was basically berated over an exhausting two-day period, and diagnosed, by the senators interrogating her, with “erotomania” and a case of man-eating professionalism. Ford’s experience—shaped by the optics of the #MeToo moment, by her whiteness and country-club roots—was different. The Republicans on the committee, likely coached by some consultant, did not overtly smear Ford. Some pretended, condescendingly, to extend her empathy. Senator Orrin Hatch, who once claimed that Hill had lifted parts of her harassment allegations against Thomas from “The Exorcist,” called Ford “pleasing,” an “attractive” witness. Instead of questioning her directly, the Republicans hired Rachel Mitchell, a female prosecutor specializing in sex crimes, to serve as their proxy. Mitchell’s fitful, sometimes aimless questioning did the ugly work of softening the Republican assault on Ford’s testimony. Ford, in any case, was phenomenal, a “witness and expert” in one, and it seemed, for a moment following her testimony, that the nation might be unable to deny her credibility.

Then Kavanaugh came in, like an eclipse. He made a show of being unprepared. Echoing Clarence Thomas, he claimed that he did not watch his accuser’s hearing. (Earlier, it was reported that he did.) “I wrote this last night,” he said, of his opening statement. “No one has seen this draft.” Alternating between weeping and yelling, he exemplified the conservative’s embrace of bluster and petulance as rhetorical tools. Going on about his harmless love of beer, spinning unbelievably chaste interpretations of what was, by all other accounts, his youthful habit of blatant debauchery, he was as Trumpian as Trump himself, louder than the loudest on Fox News. He evaded questions; he said that the allegations brought against him were “revenge” on behalf of the Clintons; he said, menacingly, that “what goes around comes around.” When Senator Amy Klobuchar calmly asked if he had ever gotten blackout drunk, he retorted, “Have you?” (He later apologized to her.)

There was, in this performance, not even a hint of the sagacity one expects from a potential Supreme Court Justice. More than presenting a convincing rebuttal to Ford’s extremely credible account, Kavanaugh—and Hatch, and Lindsey Graham—seemed to be exterminating, live, for an American audience, the faint notion that a massively successful white man could have his birthright questioned or his character held to the most basic type of scrutiny. In the course of Kavanaugh’s hearing, Mitchell basically disappeared. Republican senators apologized to the judge, incessantly, for what he had suffered. There was talk of his reputation being torpedoed and his life being destroyed. This is the nature of the conspiracy against white male power—the forces threatening it will always somehow be thwarted at the last minute.

The Hill-Thomas hearings persist in the American consciousness as a watershed moment for partisanship, for male entitlement, for testimony on sexual misconduct, for intra-racial tension and interracial affiliation. The Ford-Kavanaugh hearings will be remembered for their entrenchment of the worst impulses from that earlier ordeal. What took place on Thursday confirms that male indignation will be coddled, and the gospel of male success elevated. It confirms that there is no fair arena for women’s speech. Mechanisms of accountability will be made irrelevant. Some people walked away from 1991 enraged. The next year was said to be the Year of the Woman. Our next year, like this one, will be the Year of the Man."

The Ford-Kavanaugh Hearings Will Be Remembered As a Grotesque Display of Patriarchal Resentment | The New Yorker

Opinion | Why Brett Kavanaugh Wasn’t Believable - The New York Times

"What a study in contrasts: Where Christine Blasey Ford was calm and dignified, Brett Kavanaugh was volatile and belligerent; where she was eager to respond fully to every questioner, and kept worrying whether she was being “helpful” enough, he was openly contemptuous of several senators; most important, where she was credible and unshakable at every point in her testimony, he was at some points evasive, and some of his answers strained credulity.

Indeed, Dr. Blasey’s testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Thursday was devastating.

With the eyes of the nation on her, Dr. Blasey recounted an appalling trauma. When she was 15 years old, she said, she was sexually assaulted by Judge Kavanaugh, then a 17-year-old student at a nearby high school and now President Trump’s nominee to the Supreme Court.

Her description of the attack, which she said occurred in a suburban Maryland home on a summer night in 1982, was gut-wrenchingly specific. She said Judge Kavanaugh and his friend, Mark Judge, both of whom she described as very drunk, locked her in a second-floor room of a private home. She said Kavanaugh jumped on top of her, groped her, tried to remove her clothes and put his hand over her mouth to keep her from screaming. She said she feared he might accidentally kill her.

“The uproarious laughter between the two and their having fun at my expense,” she said, was her strongest memory.

Judge Kavanaugh, when it was his turn, was not laughing. He was yelling. He spent more than half an hour raging against Senate Democrats and the “Left” for “totally and permanently” destroying his name, his career, his family, his life. He called his confirmation process a “national disgrace.”

“You may defeat me in the final vote, but you will never get me to quit,” Judge Kavanaugh said, sounding like someone who suddenly doubted his confirmation to the Supreme Court — an outcome that seemed preordained only a couple of weeks ago.

Judge Kavanaugh’s defiant fury might be understandable coming from someone who believes himself innocent of the grotesque charges he’s facing. Yet it was also evidence of an unsettling temperament in a man trying to persuade the nation of his judicial demeanor.

We share the sorrow of every sensible American who feels stricken at the partisan spectacle playing out in Washington. Judge Kavanaugh was doubtless — and lamentably — correct in predicting that after this confirmation fight, however it ends, the bitterness is only likely to grow. As he put it in his testimony, “What goes around, comes around,” in the partisan vortex that has been intensifying in Washington for decades now. His open contempt for the Democrats on the committee also raised further questions about his own fair-mindedness, and it served as a reminder of his decades as a Republican warrior who would take no prisoners.

Judge Kavanaugh’s biggest problem was not his demeanor but his credibility, which has been called in question on multiple issues for more than a decade, and has been an issue again throughout his Supreme Court confirmation process.

On Thursday, he gave misleading answers to questions about seemingly small matters — sharpening doubts about his honesty about far more significant ones. He gave coy answers when pressed about what was clearly a sexual innuendo in his high-school yearbook. He insisted over and over that others Dr. Blasey named as attending the gathering had “said it didn’t happen,” when in fact at least two of them have said only that they don’t recall it — and one of them told a reporter that she believes Dr. Blasey.

Judge Kavanaugh clumsily dodged a number of times when senators asked him about his drinking habits. When Senator Amy Klobuchar gently pressed him about whether he’d ever blacked out from drinking, he at first wouldn’t reply directly. “I don’t know, have you?” he replied — a condescending and dismissive response to the legitimate exercise of a senator’s duty of advise and consent. (Later, after a break in the hearing, he apologized.)

Judge Kavanaugh gave categorical denials a number of times, including, at other points, that he’d ever blacked out from too much drinking. Given numerous reports now of his heavy drinking in college, such a blanket denial is hard to believe.

In contrast, Dr. Blasey bolstered her credibility not only by describing in harrowing detail what she did remember, but by being honest about what she didn’t — like the exact date of the gathering, or the address of the house where it occurred. As she pointed out, the precise details of a trauma get burned into the brain and stay there long after less relevant details fade away.

She was also honest about her ambivalence in coming forward. “I am terrified,” she told the senators in her opening remarks. And then there’s the fact that she gains nothing by coming forward. She is in hiding now with her family in the face of death threats.

Perhaps the most maddening part of Thursday’s hearing was the cowardice of the committee’s 11 Republicans, all of them men, and none of them, apparently, capable of asking Dr. Blasey a single question. They farmed that task out to a sex-crimes prosecutor named Rachel Mitchell, who tried unsuccessfully in five-minute increments to poke holes in Dr. Blasey’s story.

Eventually, as Judge Kavanaugh testified, the Republican senators ventured out from behind their shield. Doubtless seeking to ape President’s Trump style and win his approval, they began competing with each other to make the most ferocious denunciation of their Democratic colleagues and the most heartfelt declaration of sympathy for Judge Kavanaugh, in a show of empathy far keener than they managed to muster for Dr. Blasey.

Pressed over and over by Democratic senators, Judge Kavanaugh never could come up with a clear answer for why he wouldn’t also want a fair, neutral F.B.I. investigation into the allegations against him — the kind of investigation the agency routinely performs, and that Dr. Blasey has called for. At one point, though, he acknowledged that it was common sense to put some questions to other potential witnesses besides him.

When Senator Patrick Leahy asked whether the judge was the inspiration for a hard-drinking character named Bart O’Kavanaugh in a memoir about teenage alcoholism by Mr. Judge, Judge Kavanaugh replied, “You'd have to ask him.”

Asking Mr. Judge would be a great idea. Unfortunately he’s hiding out in a Delaware beach town and Senate Republicans are refusing to subpoena him.

Why? Mr. Judge is the key witness in Dr. Blasey’s allegation. He has said he has no recollection of the party or of any assault. But he hasn’t faced live questioning to test his own memory and credibility. And Dr. Blasey is far from alone in describing Judge Kavanaugh and Mr. Judge as heavy drinkers; several of Judge Kavanaugh’s college classmates have said the same.

None of these people have been called to testify before the Senate. President Trump has refused to call on the F.B.I. to look into the multiple allegations that have been leveled against the judge in the past two weeks. Instead the Republican majority on the committee has scheduled a vote for Friday morning.

There is no reason the committee needs to hold this vote before the F.B.I. can do a proper investigation, and Mr. Judge and possibly other witnesses can be called to testify under oath. The Senate, and the American people, need to know the truth, or as close an approximation as possible, before deciding whether Judge Kavanaugh should get a lifetime seat on the nation’s highest court. If the committee will not make a more serious effort, the only choice for senators seeking to protect the credibility of the Supreme Court will be to vote no."

Opinion | Why Brett Kavanaugh Wasn’t Believable - The New York Times

Thursday, September 27, 2018

Did Republicans Think Through How the Prosecutor They Brought in for the Kavanaugh-Ford Hearing Would Do Her Job? | The New Yorker

"Rachel Mitchell, the sex-crimes prosecutor from Arizona whom Republicans on the Judiciary Committee brought in to question Christine Blasey Ford, was just beginning her questioning, using a gentle, deliberate tone, when she was cut off by Senator Chuck Grassley, the committee’s chairman. Mitchell looked briefly confused, but Grassley explained: the rules of the committee stipulated that the senators would get only five minutes each to question the witness, and that those five-minute installments would alternate between Republican and Democratic members. Grassley ceded to Senator Dianne Feinstein, who got her five minutes, before Mitchell got to pick things back up, as if pressing Play on a tape recorder. Republicans brought Mitchell in to avoid the ugly scene of a uniform group of men questioning a woman bringing forward a sexual-assault accusation. But did they give any thought to how she would do her job?"

Did Republicans Think Through How the Prosecutor They Brought in for the Kavanaugh-Ford Hearing Would Do Her Job? | The New Yorker

Flashback: The Anita Hill Hearings Compared to Today - The New York Times

Opinion | Brett Kavanaugh and America’s ‘Himpathy’ Reckoning - The New York Times

"Brett Kavanaugh is a “great gentleman,” President Trump said at a White House news conference last week. “I feel so badly for him. This is not a man who deserves this.” At no point on that occasion did Mr. Trump say the name of the woman, Christine Blasey Ford, who had accused Judge Kavanaugh of sexual assault. After further allegations about Judge Kavanaugh’s behavior were reported on Sunday night, Mr. Trump doubled down: What was going on was “most unfair” to Judge Kavanaugh, who is “an outstanding person.”

When it comes to the moral deficiencies exhibited by Mr. Trump and other supporters of the judge, many critics speak about lack of empathy as the problem. It isn’t. Mr. Trump, as he has shown clearly in the Kavanaugh confirmation process, seems to have no difficulty taking another person’s perspective, and then feeling and expressing a sympathetic or congruent moral emotion.

The real problem is that the people Mr. Trump feels with and for are most frequently powerful men who have been credibly accused of serious crimes and wrongdoing. He felt sorry for Michael Flynn, referring to him as a “good guy.” More recently, he felt bad for Paul Manafort. And, in the case of Judge Kavanaugh, Mr. Trump feels sorry for a man accused of sexual assault while erasing and dismissing the perspective of his female accusers.

Mr. Trump is manifesting what I call “himpathy” — the inappropriate and disproportionate sympathy powerful men often enjoy in cases of sexual assault, intimate partner violence, homicide and other misogynistic behavior.

There is a plethora of recent cases, from the Stanford swimmer Brock Turner to the Maryland school gunman Austin Rollins, fitting this general pattern: discussion focuses excessively on the perpetrator’s perspective, on the potential pain driving him or on the loss of his bright future. And the higher a man rises in the social hierarchy, the more himpathy he tends to attract. Thus, the bulk of our collective care, consideration, respect and nurturing attention is allotted to the most privileged in our society.

Once you learn to spot himpathy, it becomes difficult not to see it everywhere: in men such as the former editor of The New York Review of Books Ian Buruma, who published a self-indulgent essay by a former Canadian talk-show host accused of sexual assault and harassment by more than 20 women; in women like the five Republicans whom CNN convened recently to voice support for Judge Kavanaugh (“Tell me, what boy hasn’t done this in high school?” asked one, shrugging himpathetically). But we’re in a moment during which himpathy is so thoroughly on display, in such a public way, that the time is ripe to push for a mass moral reckoning.

What the Kavanaugh case has revealed this week is that himpathy can, at its most extreme, become full-blown gendered sociopathy: a pathological moral tendency to feel sorry exclusively for the alleged male perpetrator — it was too long ago; he was just a boy; it was a case of mistaken identity — while relentlessly casting suspicion upon the female accusers. It also reveals the far-ranging repercussions of this worldview: It’s no coincidence that many of those who himpathize with Judge Kavanaugh to the exclusion of Dr. Blasey are also avid abortion opponents, a position that requires a refusal to empathize with girls and women facing an unwanted pregnancy.

What makes himpathy so difficult to counter is that the mechanisms underlying it are partly moral in nature: Sympathy and empathy are pro-social moral emotions, which makes it especially hard to convince people that when they skew toward the powerful and against the vulnerable, they become a source of systemic injustice. So, for those for whom himpathy is a mental habit prompted by biased social forces, and not an entrenched moral outlook, the first step to solving the problem is simply learning to recognize when it’s at work, and to be wary of its biasing influence.

The second step to solving the problem of himpathy is listening to girls and women. Do you wonder why someone might not come forward to report sexual assault as an adolescent girl? Listen to Dr. Blasey, who told The Washington Post that at the time she was terrified that she would be in trouble if her parents realized she had been at a party where teenagers were drinking. She recalled thinking: “I’m not ever telling anyone this. This is nothing, it didn’t happen, and he didn’t rape me.” It wasn’t until years later, with the help of a therapist, that she emerged from this denial and recognized the episode as traumatic.

In other words, like many women, Dr. Blasey needed a long time to break a silence born out of society’s entrenched deference to privileged men. It’s a deference that Mr. Trump and Judge Kavanaugh’s other supporters are now demonstrating vividly.

Kate Manne is an assistant professor of philosophy at Cornell and the author of “Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny.”

Opinion | Brett Kavanaugh and America’s ‘Himpathy’ Reckoning - The New York Times

Opinion | ‘Mean Drunk’ vs. Teenage Girls - The New York Times

"These accusations don’t paint Brett Kavanaugh as just a cad, but as a lascivious predator.

"And then there were three.

Three women — Christine Blasey Ford, Deborah Ramirez and Julie Swetnick — are now accusing Brett Kavanaugh of sexual misconduct as a teenager and young adult. The allegations include assault, attempted rape and, now, that he and other boys attempted “to cause girls to become inebriated and disoriented so that they could then be ‘gang raped’ in a side room or bedroom by a ‘train’ of numerous boys.”

Swetnick, the latest accuser, described Kavanaugh as a “mean drunk.”

This is explosive, extraordinary stuff.

However, Kavanaugh has categorically denied that any of this ever happened.

In an interview on Fox News, Kavanaugh said that he had always “treated women with dignity and respect” and that he “did not have sexual intercourse or anything close to sexual intercourse in high school or for many years thereafter.”

I must say that I found his specification of sexual “intercourse” interesting here. First, sexual assault doesn’t require intercourse. Second, one can be sexually intimate — or sexually violated — without intercourse. That struck me as a bit of carefully chosen lawyer-speak.

To be clear, these accusations don’t paint Kavanaugh as just a cad, but as a lascivious predator. If these things are true, not only must he never be seated on the Supreme Court, he must also lose his current judgeship.

According to Kavanaugh’s prepared written testimony for his hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Thursday, he will cede a little ground on bad behavior:

“I spent most of my time in high school focused on academics, sports, church and service. But I was not perfect in those days, just as I am not perfect today. I drank beer with my friends, usually on weekends. Sometimes I had too many. In retrospect, I said and did things in high school that make me cringe now.”

But he still denies sexual misconduct.

Either these women are all lying about Kavanaugh, or he is lying in his denial. But the one thing that is absolutely true here is that someone is lying, and multiple people may be doing so.

This is not a small lie. The direction of the Supreme Court may hinge on it. Republicans are proceeding at a reckless pace because they fear that if Kavanaugh is not confirmed before the midterm elections, the Democrats have a small chance of taking control of the Senate and could then stall President Trump’s nominations or confirm only a more moderate nominee.

Democrats are banking on much the same, but there is also a principled and moral argument, aside from political posturing, to allow all three accusers to testify under oath, to call additional witnesses and to order an investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Indeed, at this point, the lying is as consequential as the accusations. Kavanaugh has so categorically denied the accusations, leaving no room whatsoever for the possibility that they are true, that one must assume that he is absolutely convinced of his own innocence, or, instead, that he’s a bona fide psychopath, like the man who nominated him.

The latter is a possibility that we cannot risk, not with the future of the court hanging in the balance.

We must grind this process to a halt until we have exhausted every possible investigative option and every fact has been uncovered.

Not doing so is a dereliction of duty and a betrayal of the country that threatens to further and irreparably damage the integrity of the court.

But of course the members of this Republican Party, strung out on Trumpism, care nothing about duty and patriotism. They care only about appeasing Trump’s base, delivering him a justice who believes in insulating presidents from prosecution and in realizing a decades-old Republican fever dream of achieving a solid conservative majority on the court.

A new NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll found this week that more people now oppose Kavanaugh than support him; more believe Blasey is telling the truth about her encounter at a party with Kavanaugh than believe he is; and 59 percent believe that if Blasey’s sexual assault charge is true, Kavanaugh should not be confirmed.

But it seems that Kavanaugh, Trump and Republicans in the Senate do not want to put in any of the time or work to find that truth. Instead, we’ve been promised a show hearing, a competition of narratives and styles of presentation, a contest of contrivances from which we are expected to judge credibility.

This is a sham, and Republicans should be ashamed. However, one cannot display what one does not possess. This is a brazen attempt to smother truth in order to advance the career of a man who would spend the rest of his life tasked with discerning truth.

They want to anoint a justice by miscarrying justice."

Opinion | ‘Mean Drunk’ vs. Teenage Girls - The New York Times

Wednesday, September 26, 2018

Christine Blasey Ford’s opening testimony - The Washington Post

"Christine Blasey Ford, the California professor who has accused Supreme Court nominee Brett M. Kavanaugh of sexual assault at a party while the two were in high school, will testify Thursday in . Ford will face questions from committee Democrats and a prosecutor representing Republicans before an audience of millions on television and online across the country, 11 days after she came forward with her allegation . Kavanaugh has denied the accusations.

Below are her prepared opening remarks, which we are annotating. To view the annotations, click on the yellow, highlighted text. Here are .

Chairman Grassley, Ranking Member Feinstein, Members of the Committee. My name is Christine Blasey Ford. I am a Professor of Psychology at Palo Alto University and a Research Psychologist at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

I was an undergraduate at the University of North Carolina and earned my degree in Experimental Psychology in 1988. I received a Master’s degree in 1991 in Clinical Psychology from Pepperdine University. In 1996, I received a PhD in Educational Psychology from the University of Southern California. I earned a Master’s degree in Epidemiology from the Stanford University School of Medicine in 2009.

I have been married to Russell Ford since 2002 and we have two children.

I am here today not because I want to be. I am terrified. I am here because I believe it is my civic duty to tell you what happened to me while Brett Kavanaugh and I were in high school. I have described the events publicly before. I summarized them in my letter to Ranking Member Feinstein, and again in my letter to Chairman Grassley. I understand and appreciate the importance of your hearing from me directly about what happened to me and the impact it has had on my life and on my family.

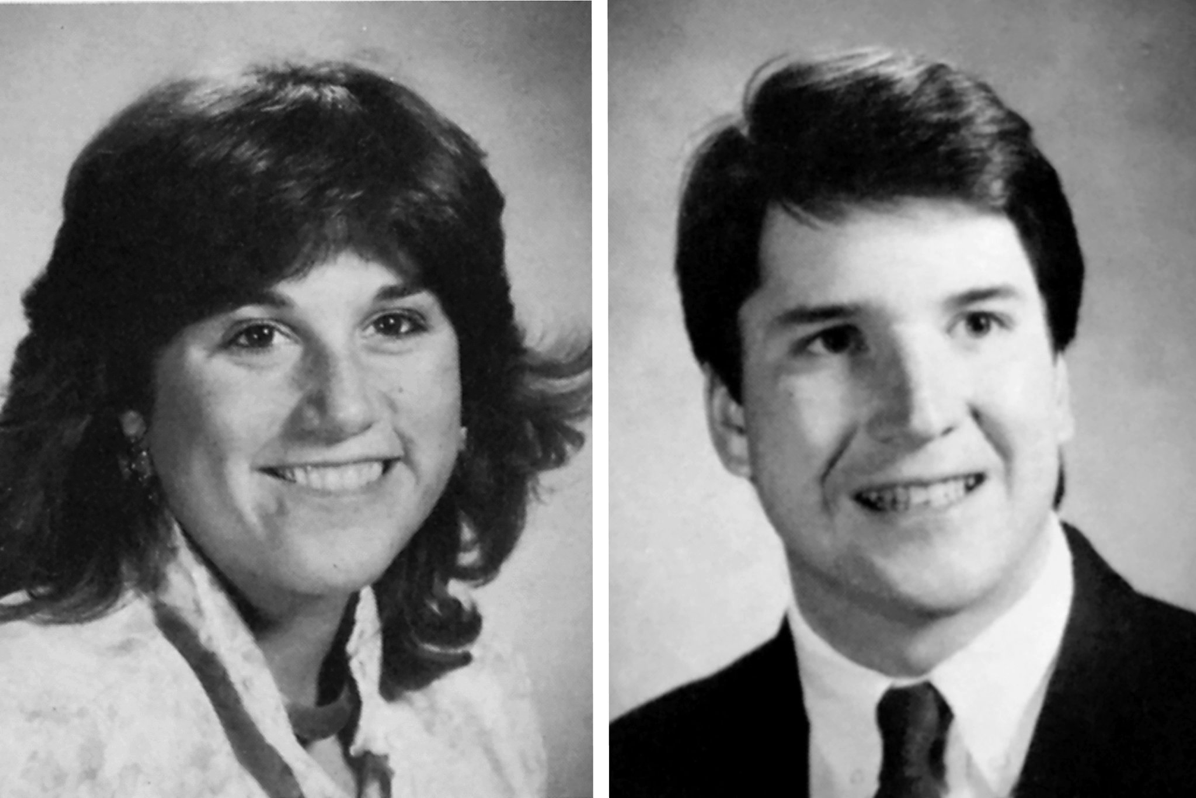

I grew up in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. I attended the Holton-Arms School in Bethesda, Maryland, from 1980 to 1984. Holton-Arms is an all-girls school that opened in 1901. During my time at the school, girls at Holton-Arms frequently met and became friendly with boys from all-boys schools in the area, including Landon School, Georgetown Prep, Gonzaga High 2 School, country clubs, and other places where kids and their families socialized. This is how I met Brett Kavanaugh, the boy who sexually assaulted me.

In my freshman and sophomore school years, when I was 14 and 15 years old, my group of friends intersected with Brett and his friends for a short period of time. I had been friendly with a classmate of Brett’s for a short time during my freshman year, and it was through that connection that I attended a number of parties that Brett also attended. We did not know each other well, but I knew him and he knew me. In the summer of 1982, like most summers, I spent almost every day at the Columbia Country Club in Chevy Chase, Maryland swimming and practicing diving.

One evening that summer, after a day of swimming at the club, I attended a small gathering at a house in the Chevy Chase/Bethesda area. There were four boys I remember being there: Brett Kavanaugh, Mark Judge, P.J. Smyth, and one other boy whose name I cannot recall. I remember my friend Leland Ingham attending. I do not remember all of the details of how that gathering came together, but like many that summer, it was almost surely a spur of the moment gathering. I truly wish I could provide detailed answers to all of the questions that have been and will be asked about how I got to the party, where it took place, and so forth. I don’t have all the answers, and I don’t remember as much as I would like to. But the details about that night that bring me here today are ones I will never forget. They have been seared into my memory and have haunted me episodically as an adult.

When I got to the small gathering, people were drinking beer in a small living room on the first floor of the house. I drank one beer that evening. Brett and Mark were visibly drunk. Early in the evening, I went up a narrow set of stairs leading from the living room to a second floor to use the bathroom. When I got to the top of the stairs, I was pushed from behind into a bedroom. I couldn’t see who pushed me. Brett and Mark came into the bedroom and locked the door behind 3 them. There was music already playing in the bedroom. It was turned up louder by either Brett or Mark once we were in the room. I was pushed onto the bed and Brett got on top of me. He began running his hands over my body and grinding his hips into me. I yelled, hoping someone downstairs might hear me, and tried to get away from him, but his weight was heavy. Brett groped me and tried to take off my clothes. He had a hard time because he was so drunk, and because I was wearing a one-piece bathing suit under my clothes. I believed he was going to rape me. I tried to yell for help. When I did, Brett put his hand over my mouth to stop me from screaming. This was what terrified me the most, and has had the most lasting impact on my life. It was hard for me to breathe, and I thought that Brett was accidentally going to kill me. Both Brett and Mark were drunkenly laughing during the attack. They both seemed to be having a good time. Mark was urging Brett on, although at times he told Brett to stop. A couple of times I made eye contact with Mark and thought he might try to help me, but he did not.

During this assault, Mark came over and jumped on the bed twice while Brett was on top of me. The last time he did this, we toppled over and Brett was no longer on top of me. I was able to get up and run out of the room. Directly across from the bedroom was a small bathroom. I ran inside the bathroom and locked the door. I heard Brett and Mark leave the bedroom laughing and loudly walk down the narrow stairs, pin-balling off the walls on the way down. I waited and when I did not hear them come back up the stairs, I left the bathroom, ran down the stairs, through the living room, and left the house. I remember being on the street and feeling an enormous sense of relief that I had escaped from the house and that Brett and Mark were not coming after me.

Brett’s assault on me drastically altered my life. For a very long time, I was too afraid and ashamed to tell anyone the details. I did not want to tell my parents that I, at age 15, was in a house without any parents present, drinking beer with boys. I tried to convince myself that because Brett 4 did not rape me, I should be able to move on and just pretend that it had never happened. Over the years, I told very few friends that I had this traumatic experience. I told my husband before we were married that I had experienced a sexual assault. I had never told the details to anyone until May 2012, during a couples counseling session. The reason this came up in counseling is that my husband and I had completed an extensive remodel of our home, and I insisted on a second front door, an idea that he and others disagreed with and could not understand. In explaining why I wanted to have a second front door, I described the assault in detail. I recall saying that the boy who assaulted me could someday be on the U.S. Supreme Court and spoke a bit about his background. My husband recalls that I named my attacker as Brett Kavanaugh.

After that May 2012 therapy session, I did my best to suppress memories of the assault because recounting the details caused me to relive the experience, and caused panic attacks and anxiety. Occasionally I would discuss the assault in individual therapy, but talking about it caused me to relive the trauma, so I tried not to think about it or discuss it. But over the years, I went through periods where I thought about Brett’s attack. I confided in some close friends that I had an experience with sexual assault. Occasionally I stated that my assailant was a prominent lawyer or judge but I did not use his name. I do not recall each person I spoke to about Brett’s assault, and some friends have reminded me of these conversations since the publication of The Washington Post story on September 16, 2018. But until July 2018, I had never named Mr. Kavanaugh as my attacker outside of therapy.

This all changed in early July 2018. I saw press reports stating that Brett Kavanaugh was on the “short list” of potential Supreme Court nominees. I thought it was my civic duty to relay the information I had about Mr. Kavanaugh’s conduct so that those considering his potential nomination would know about the assault.

On July 6, 2018, I had a sense of urgency to relay the information to the Senate and the President as soon as possible before a nominee was selected. I called my congressional representative and let her receptionist know that someone on the President’s shortlist had attacked me. I also sent a message to The Washington Post’s confidential tip line. I did not use my name, but I provided the names of Brett Kavanaugh and Mark Judge. I stated that Mr. Kavanaugh had assaulted me in the 1980s in Maryland. This was an extremely hard thing for me to do, but I felt I couldn’t NOT do it. Over the next two days, I told a couple of close friends on the beach in California that Mr. Kavanaugh had sexually assaulted me. I was conflicted about whether to speak out.

On July 9, 2018, I received a call from the office of Congresswoman Anna Eshoo after Mr. Kavanaugh had become the nominee. I met with her staff on July 11 and with her on July 13, describing the assault and discussing my fear about coming forward. Later, we discussed the possibility of sending a letter to Ranking Member Feinstein, who is one of my state’s Senators, describing what occurred. My understanding is that Representative Eshoo’s office delivered a copy of my letter to Senator Feinstein’s office on July 30, 2018. The letter included my name, but requested that the letter be kept confidential.

My hope was that providing the information confidentially would be sufficient to allow the Senate to consider Mr. Kavanaugh’s serious misconduct without having to make myself, my family, or anyone’s family vulnerable to the personal attacks and invasions of privacy we have faced since my name became public. In a letter on August 31, 2018, Senator Feinstein wrote that she would not share the letter without my consent. I greatly appreciated this commitment. All sexual assault victims should be able to decide for themselves whether their private experience is made public.

As the hearing date got closer, I struggled with a terrible choice: Do I share the facts with the Senate and put myself and my family in the public spotlight? Or do I preserve our privacy and allow the Senate to make its decision on Mr. Kavanaugh’s nomination without knowing the full truth about his past behavior?

I agonized daily with this decision throughout August and early September 2018. The sense of duty that motivated me to reach out confidentially to The Washington Post, Representative Eshoo’s office, and Senator Feinstein’s office was always there, but my fears of the consequences of speaking out started to increase.

During August 2018, the press reported that Mr. Kavanaugh’s confirmation was virtually certain. His allies painted him as a champion of women’s rights and empowerment. I believed that if I came forward, my voice would be drowned out by a chorus of powerful supporters. By the time of the confirmation hearings, I had resigned myself to remaining quiet and letting the Committee and the Senate make their decision without knowing what Mr. Kavanaugh had done to me.

Once the press started reporting on the existence of the letter I had sent to Senator Feinstein, I faced mounting pressure. Reporters appeared at my home and at my job demanding information about this letter, including in the presence of my graduate students. They called my boss and coworkers and left me many messages, making it clear that my name would inevitably be released to the media. I decided to speak out publicly to a journalist who had responded to the tip I had sent to The Washington Post and who had gained my trust. It was important to me to describe the details of the assault in my own words.

Since September 16, the date of The Washington Post story, I have experienced an outpouring of support from people in every state of this country. Thousands of people who have had their lives dramatically altered by sexual violence have reached out to share their own experiences with me and have thanked me for coming forward. We have received tremendous support from friends and our community.

At the same time, my greatest fears have been realized – and the reality has been far worse than what I expected. My family and I have been the target of constant harassment and death threats. I have been called the most vile and hateful names imaginable. These messages, while far fewer than the expressions of support, have been terrifying to receive and have rocked me to my core. People have posted my personal information on the internet. This has resulted in additional emails, calls, and threats. My family and I were forced to move out of our home. Since September 16, my family and I have been living in various secure locales, with guards. This past Tuesday evening, my work email account was hacked and messages were sent out supposedly recanting my description of the sexual assault.

Apart from the assault itself, these last couple of weeks have been the hardest of my life. I have had to relive my trauma in front of the entire world, and have seen my life picked apart by people on television, in the media, and in this body who have never met me or spoken with me. I have been accused of acting out of partisan political motives. Those who say that do not know me. I am a fiercely independent person and I am no one’s pawn. My motivation in coming forward was to provide the facts about how Mr. Kavanaugh’s actions have damaged my life, so that you can take that into serious consideration as you make your decision about how to proceed. It is not my responsibility to determine whether Mr. Kavanaugh deserves to sit on the Supreme Court. My responsibility is to tell the truth.

I understand that the Majority has hired a professional prosecutor to ask me some questions, and I am committed to doing my very best to answer them. At the same time, because the Committee Members will be judging my credibility, I hope to be able to engage directly with each of you.

At this point, I will do my best to answer your questions."

Christine Blasey Ford’s opening testimony - The Washington Post

The Body Of Poverty

Attorney: Republicans skipped call with second Kavanaugh accuser John Clune, attorney for Debbie Ramirez, the second woman to accuse Donald Trump's pick for Supreme Court Brett Kavanaugh of sexual misconduct, talks with Rachel Maddow about the difficulty his client is having getting her story heard by the Senate Judiciary Committee.

In a Culture of Privilege and Alcohol at Yale, Her World Converged With Kavanaugh’s - The New York Times

"Last week, more than 30 years after they graduated from Yale, Deborah Ramirez contacted her old friend James Roche.

Something bad had happened to her during a night of drinking in the residence hall their freshman year, she said, and she wondered if he recalled her mentioning it at the time.Image

Mr. Roche, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur, said he had no knowledge of the episode that Ms. Ramirez was trying to piece together, with her memory faded by the years and clouded by that night’s alcohol use.

Days later, in a New Yorker story, Ms. Ramirez alleged that Judge Brett M. Kavanaugh, President Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, exposed himself to her at a dorm party. Mr. Roche, a former roommate of the judge, believes her account, he said, and supports her decision to speak out.

“I think she feels a duty to come forward,” Mr. Roche said. “And I think she’s scared to death of it.”

Ms. Ramirez’s allegation — she is the second woman to level claims of sexual misconduct against Judge Kavanaugh — has roiled an already tumultuous confirmation process and riven the Yale community.

More than 2,200 Yale women have signed a letter of support for Ms. Ramirez; a similar letter has been circulating among Yale men. Dozens of students, dressed in black, staged a protest at Yale Law School on Monday, urging that the claims against Judge Kavanaugh be taken seriously. Others went to Washington to hold signs outside the Supreme Court, just days before the Senate Judiciary Committee is scheduled to hear from Judge Kavanaugh’s first accuser, Christine Blasey Ford.

Judge Kavanaugh, 53, denies the allegations of both women, describing the accusations as “smears” orchestrated by Democrats. Before they arose, more than than 100 Yale students, alumni and faculty members endorsed his nomination to the high court in an open letter. Separately, 23 Yale Law classmates urged Judge Kavanaugh’s confirmation in a letter to the leaders of the Senate Judiciary Committee, noting his “considerable intellect, friendly manner, good sense of humor and humility.”

At a protest at Yale Law School on Monday, students urged that the sexual misconduct claims against Judge Kavanaugh be taken seriously.Daniel Zhao/Yale Daily NewsThe allegation by Ms. Ramirez, also 53, stems from an incident she said occurred during the 1983-84 school year, when she and Judge Kavanaugh were freshmen.

Like most first-year students, they lived on Old Campus, a quadrangle of Gothic architecture on the Yale grounds. Their social circles included mutual friends.

But they came from worlds apart. Ms. Ramirez arrived at the rarefied halls of Yale from Shelton, Conn., a town just 30 minutes away, the daughter of a telephone company lineman and a medical technician. She attended a coed Catholic high school, St. Joseph, that was predominantly white but had a number of minority students, including Ms. Ramirez, whose father was Puerto Rican.

She worked on the high school paper, belonged to a literary club and was a shy but “brilliant student,” remembered a friend, Dana DeTullio Bauro. “We were not surprised at all that she went to Yale.”

Deborah Ramirez was a shy but “brilliant student” in high school, a friend remembers.At college, Ms. Ramirez put in long hours working at a residential dining hall and cleaning dorm rooms ahead of class reunions, common jobs for students who had to scrape together money for tuition. Fellow student dining hall employees described her as sweet, sunny and hard-working. Jo Miller, one of those students, said she “was a very energetic, very smiley woman.”

She had been a cheerleader her freshman year, played intramural softball and water polo, and served on her residential college’s student council.

But she saw herself as an outsider at Yale, Mr. Roche said, where many of her classmates were wealthier and more traveled. Friends from back then described her as not particularly confident in a place full of other high school standouts. Ms. Ramirez declined to be interviewed for this article, but her lawyer, Stan Garnett, noted that “she did not come from race or class privilege or have the advantage other students had when entering the university.”

She also found herself in an alcohol-infused culture. “Her whole circle happened to be a drinking circle,” said Victoria Beach, who served as president of the student council when Ms. Ramirez was a member. Elizabeth Swisher, a Seattle physician who roomed with Ms. Ramirez for three years at Yale, recalled, “She was very innocent coming into college.” She added, “I felt an obligation early in freshman year to protect her.”

Ms. Ramirez, front row on the right, cheering at a Yale game.Judge Kavanaugh had attended Georgetown Preparatory, an elite Jesuit school in suburban Washington, where his parents moved in the capital’s political circles. His family was well-off, with his father a lobbyist and his mother a judge. At Yale, he seemed to settle in quickly with a crowd not unlike his high school friends.

Although he was not a varsity athlete — he was on the junior varsity basketball team and played intramural football, softball and basketball — Judge Kavanaugh hung out with rowdy jocks, many of them members of his fraternity, Delta Kappa Epsilon.

On a liberal campus known for its scholarship, the DKEs stood out for their hard partying and, some women students claimed, misogyny. During Judge Kavanaugh’s time there — 15 or so years after women arrived — some fraternity brothers paraded around campus displaying women’s underwear they had filched, drawing criticism.

DKE was a “huge party fraternity,” said a former classmate, Sarah Dry. “Lots of drunken parties.”

The DKE pledge process was widely seen on campus as degrading. An opinion piece in The Yale Daily News in 1986 said that pledges were forced to walk around campus reading Penthouse magazine aloud and yelling lines like “I’m a butt-hole, sir.”

One woman remembers Judge Kavanaugh’s wearing a leather football helmet while drinking and approaching her on campus the night he was tapped for DKE. She described his grabbing his crotch, hopping on one leg and chanting: “I’m a geek, I’m a geek, I’m a power tool. When I sing this song, I look like a fool.”

Nearly a dozen people who knew him well or socialized with him said Judge Kavanaugh was a heavy drinker in college. Dr. Swisher said she saw him “very drunk” a number of times. Mr. Roche, his former freshmen year roommate, described his stumbling in at all hours of the night.

In a statement, Kerri Kupec, a White House spokeswoman, played down the descriptions of Mr. Kavanaugh’s heavy drinking at Yale without disputing them. “This is getting absurd,” she said. “No one has claimed Judge Kavanaugh didn’t drink in high school or college.”

Ms. Kupec noted that in a Fox News interview on Monday, Mr. Kavanaugh acknowledged that “all of us have probably done things we look back on in high school and regret or cringe a bit.”

Some former students cautioned against associating Judge Kavanaugh with DKE’s heavy partying contingent. “They were a typical fraternity that served alcohol, but I don’t recall ever seeing Brett Kavanaugh drunk,” said John Risley, who overlapped with Judge Kavanaugh at Yale and was friendly with members of DKE.

One night, Ms. Ramirez told The New Yorker, Judge Kavanaugh exposed himself to her during a drinking game in a dorm suite.

Sitting in a circle with a small group of students, she recalled, people selected who had to take a drink, and Ms. Ramirez said she was chosen frequently. She became drunk, her head “foggy,” she recalled. As the game continued, a male student began playing with a plastic dildo, pointing it around the room.

Suddenly, Ms. Ramirez claimed, she saw a penis in front of her face.

When she remarked that it wasn’t real, the others students began laughing, with one man telling her to “kiss it,” she told The New Yorker in an interview. Then, as she moved to push it away, she alleged, she saw Judge Kavanaugh standing, laughing and pulling up his pants.

Neither The New Yorker nor The New York Times, which attempted to verify Ms. Ramirez’s story last week, were able to find witnesses acknowledging the episode. (The Times did not obtain an interview with Ms. Ramirez.) The New Yorker, however, reported that a fellow student, whom the publication did not identify, confirmed having learned of the incident — and Judge Kavanaugh’s alleged role in it — within a day or two after it happened.

“She was very innocent coming into college,” Ms. Ramirez’s college roommate said of her.Ms. Ramirez initially told friends she had memory gaps and was not certain that Judge Kavanaugh was the person who exposed himself, as she related to Mr. Roche and some other old classmates last week. But, after six days of assessing her memories, The New Yorker reported, she said she was confident that Judge Kavanaugh was the man who had humiliated her.

Her lawyers declined to comment further on the episode.

Chris Dudley, a friend and supporter of Mr. Kavanaugh who belonged to DKE and went on to play professional basketball, says the allegations don’t square with the man he knows. “That’s just not Brett,” he said. “That’s not in his character.”

Ms. Ramirez told few people about the incident at the time, she has said to former classmates, because she felt embarrassed and wanted to forget about it. While she and Judge Kavanaugh were not close friends, they continued to cross paths at Yale and beyond. In 1997, for example, they both attended a wedding of classmates, and appeared in a group photo.

Some of her closest Yale friends said they lost touch with Ms. Ramirez in the last decade. That was in part because she became more politically liberal and conscious of her Latino roots and no longer felt as comfortable among her Yale cohort, several friends said she told them.

Over the past 16 years, Ms. Ramirez, a registered Democrat who lives in Boulder, Colo., with her husband, Vikram Shah, a technology consultant, has worked with a domestic violence organization, both as a volunteer and in a paid position. She joined the board of the organization in 2014.

Ms. Ramirez also works for the Boulder County housing department, where she coordinates funding for low-income families and recruits volunteers.

Anne Tapp, executive director of the domestic violence organization, described Ms. Ramirez as remarkable, compassionate and trustworthy, and said that the two women had discussed multiple times in recent days whether she would come forward with her account about Judge Kavanaugh. Ms. Tapp said that she had tried to support her. “She has struggled over the past week or so to come to the decision to share her very personal story,” Ms. Tapp said.

Several former students who worked in the dining hall along with Ms. Ramirez and her younger sister, Denise, who is also a Yale graduate, did not know of the incident Ms. Ramirez described and have not seen her in years, they said in interviews. But they said they knew her to be an honest person in college.

Ms. Ramirez got involved in intramural sports, cheerleading and student council at Yale.“She wasn’t manipulative,” said Lisanne Sartor, a former Yale student who is now a writer and director. “What you saw was what you got. This was not someone seeking the spotlight.”

Mr. Roche, the friend she called last week, described her similarly.

“She was bright eyed and guileless, compared to the sophisticated and often aggressive population you find at Yale,” he said in an interview. “The idea that she would make something like this up is inconceivable,” he added. “It’s not consistent with who I know her to be.”

Reporting was contributed by Rebecca Ruiz, Emily Steel, Jo Becker, Grace Ashford, Steve Eder and Kitty Bennett.

Tuesday, September 25, 2018

Brett Kavanaugh allegations and male bonding.

For what it’s worth, and absent evidence or allegations to the contrary, I believe Brett Kavanaugh’s claim that he was a virgin through his teens. I believe it in part because it squares with some of the oddities I’ve had a hard time understanding about his alleged behavior: namely, that both allegations are strikingly different from other high-profile stories the past year, most of which feature a man and a woman alone. And yet both the Kavanaugh accusations share certain features: There is no penetrative sex, there are always male onlookers, and, most importantly, there’s laughter. In each case the other men—not the woman—seem to be Kavanaugh’s true intended audience. In each story, the cruel and bizarre act the woman describes—restraining Christine Blasey Ford and attempting to remove her clothes in her allegation, and in Deborah Ramirez’s, putting his penis in front of her face—seems to have been done in the clumsy and even manic pursuit of male approval. Even Kavanaugh’s now-notorious yearbook page, with its references to the “100 kegs or bust” and the like, seems less like an honest reflection of a fun guy than a representation of a try-hard willing to say or do anything as long as his bros think he’s cool. In other words: The awful things Kavanaugh allegedly did only imperfectly correlate to the familiar frame of sexual desire run amok; they appear to more easily fit into a different category—a toxic homosociality—that involves males wooing other males over the comedy of being cruel to women.