The Transatlantic Slave Trade

"Table of Contents

- The European Influence on Africa

- The Barbarity of the Middle Passage

- Slavery in the Americas

- New England Trafficking

- A Trafficking-Based Economy

- Industries Reliant on Enslaved Labor

- Laws Limiting Freedom

- The Port of Boston

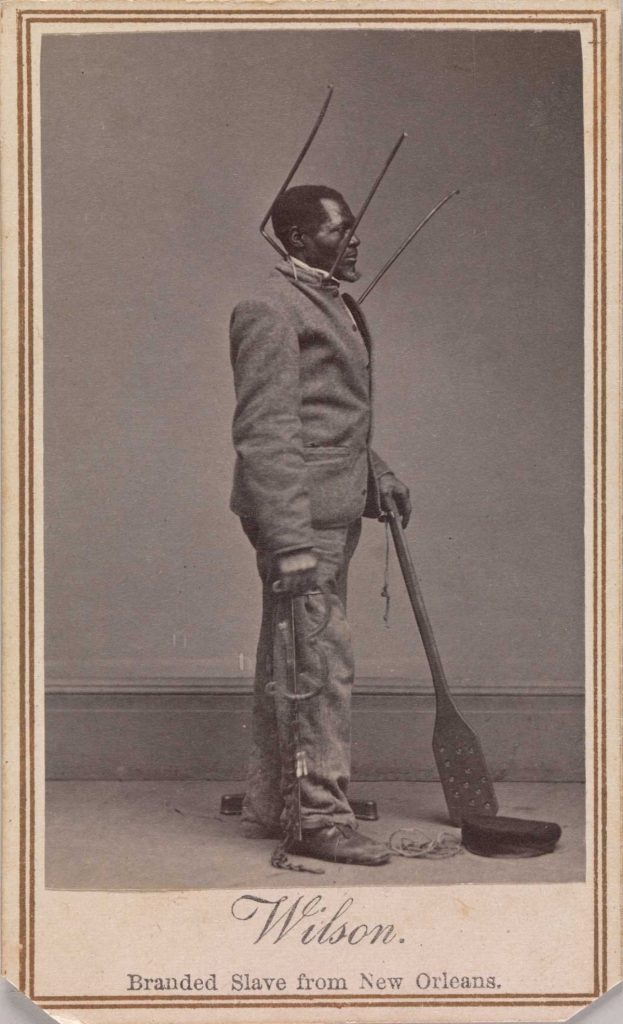

- Controlling Enslaved People

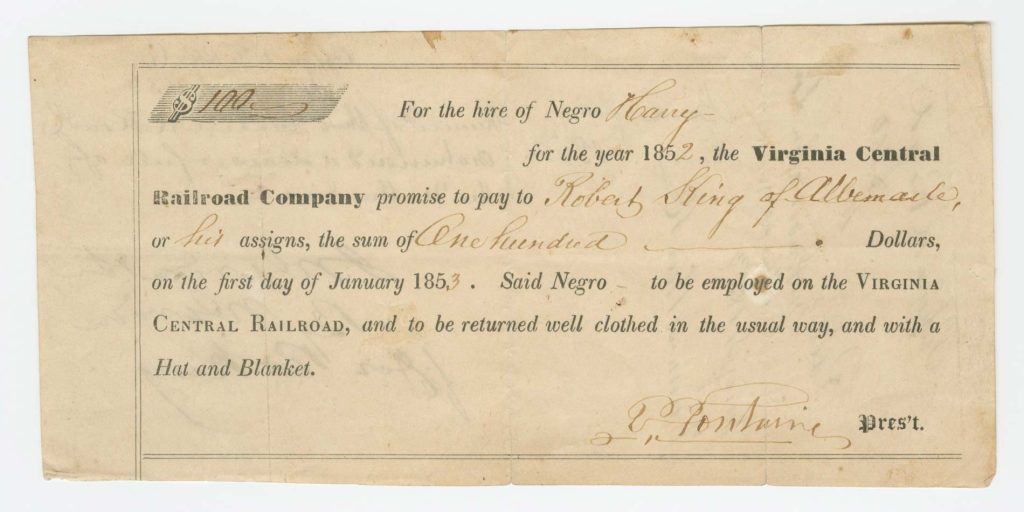

- Profiting from Trafficking

- After Abolition

- Trading on Wall Street

- Laws Targeting Black People

- An Economy Founded on Slavery

- Post-War Racial Discrimination

- A Hub for Human Trafficking

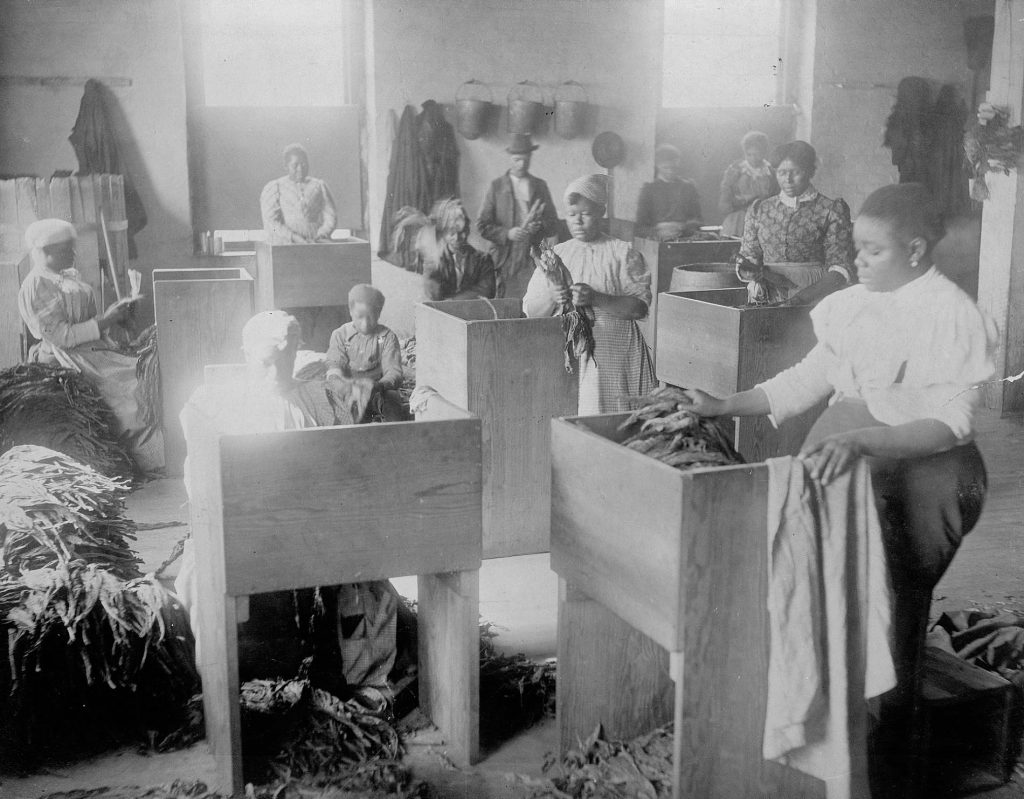

- Work of Enslaved People

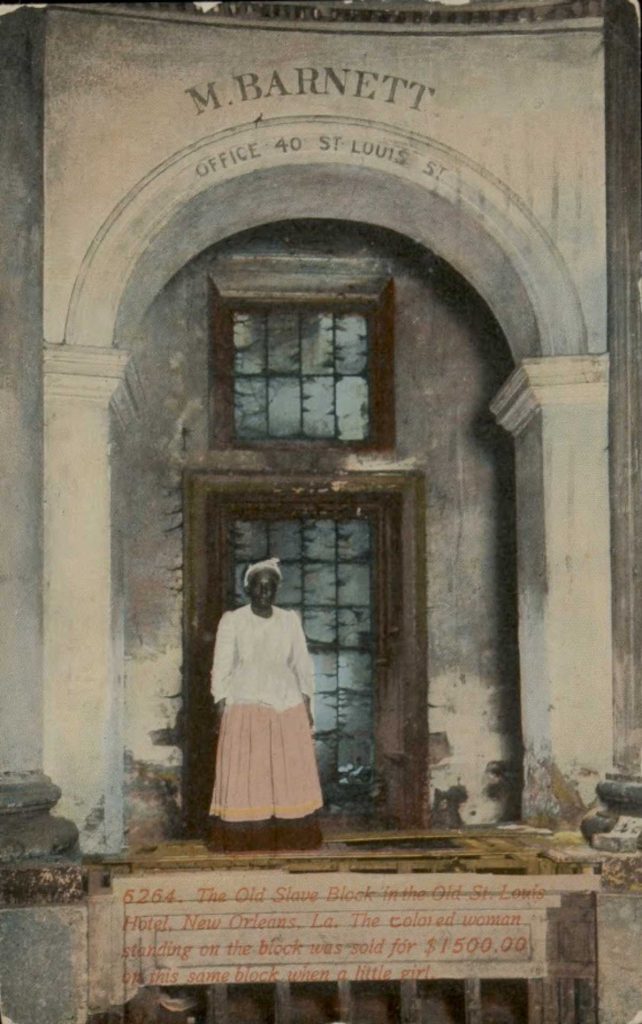

- Separating Families

- Controlling Black People

- A Legacy of Racial Bias

- Tobacco Drives Trafficking

- Legislating Hereditary Enslavement

- Laws Controlling Lives

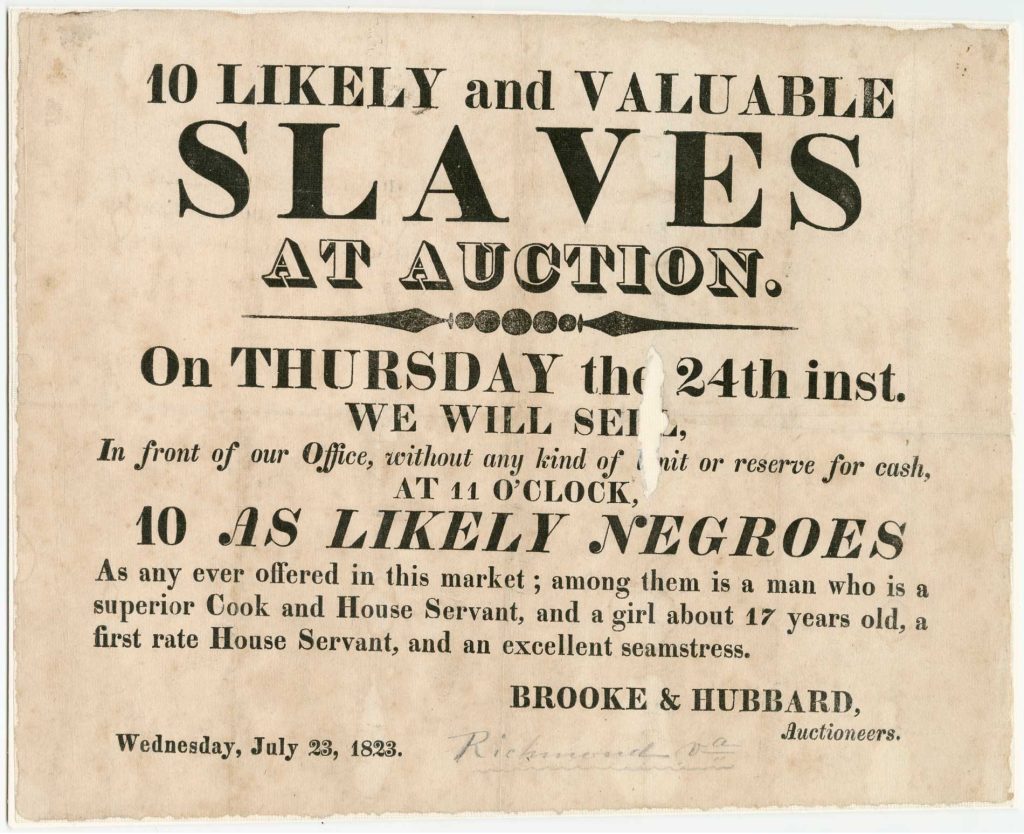

- The Domestic Slave Trade

- A Trafficking Hub

- An Enslavement-Based Economy

- Suppressing Black Resistance

- Center of the Domestic Slave Trade

- Trafficking for Rice and Indigo

- North Carolina Trafficking

- Resistance to Enslavement

- “Carolina Gold”

- Centrality of African Culture

- Wealth Through Exploitation

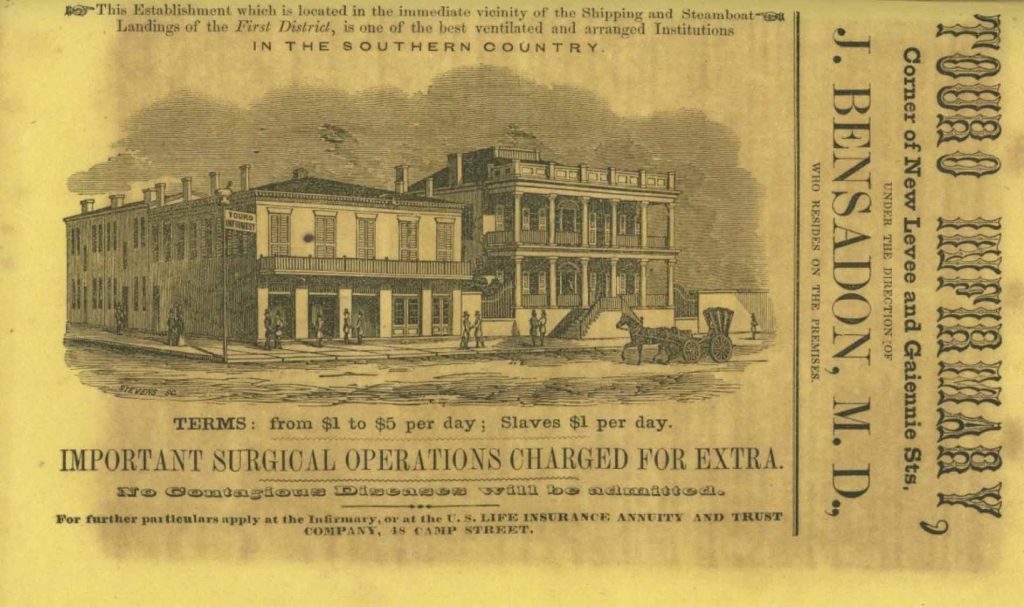

- Spanish and French Trafficking

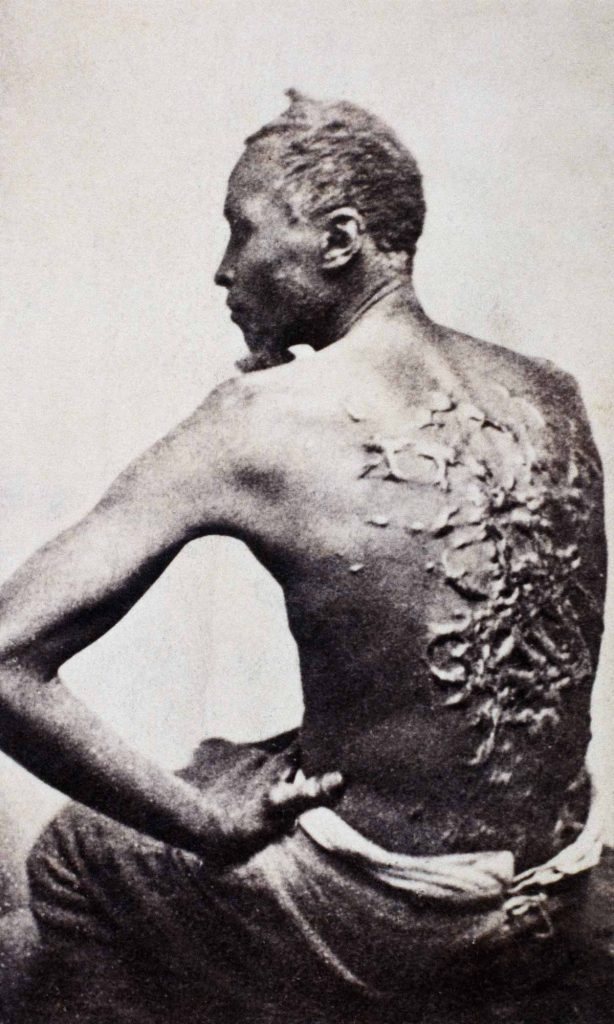

- Enslavement Conditions

- Trafficking Surges in the 18th Century

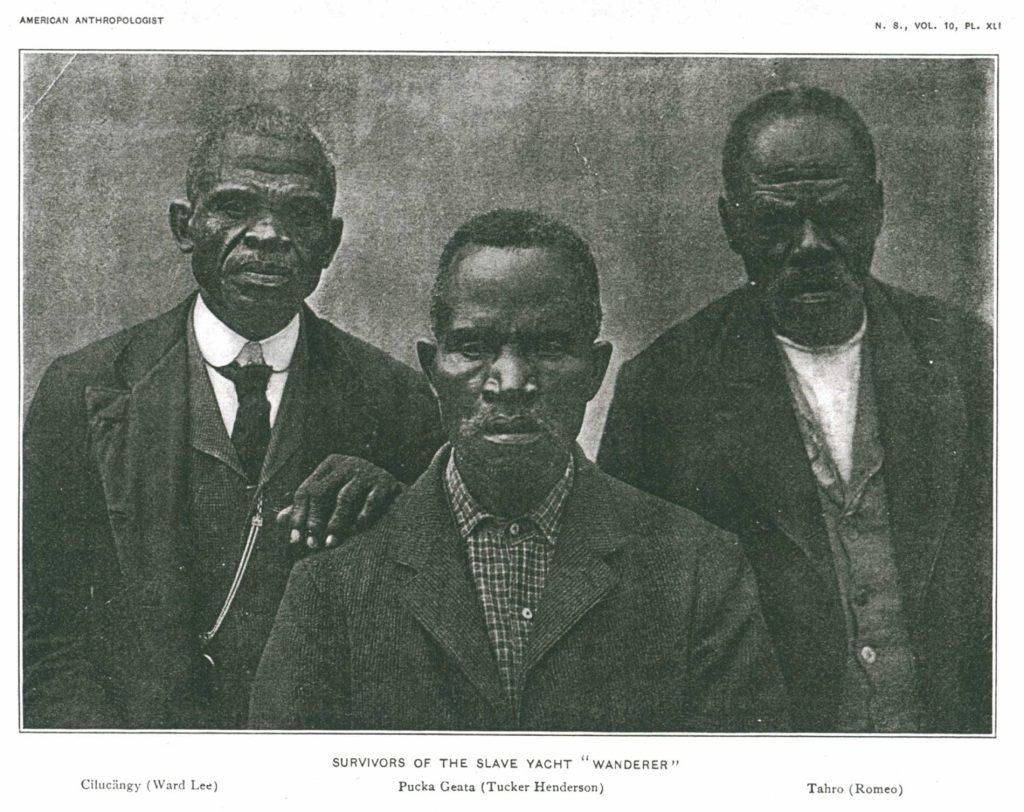

- Illegal Transatlantic Trafficking

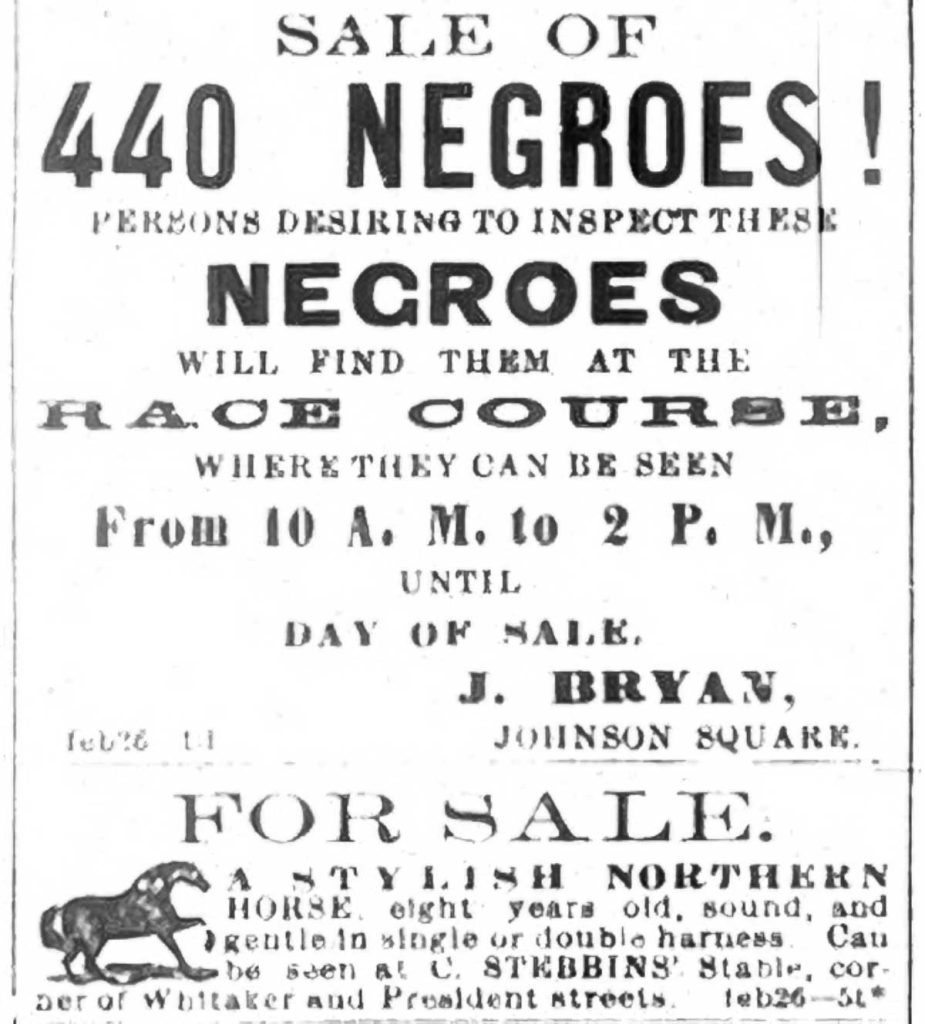

- Trafficking in Savannah

- Urban Enslavement

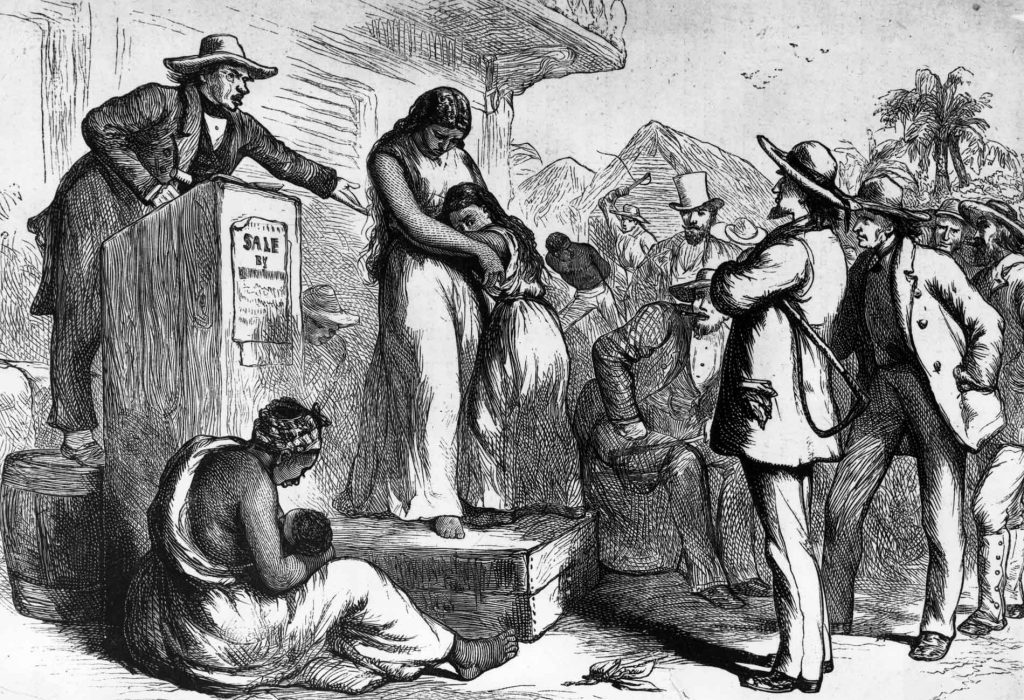

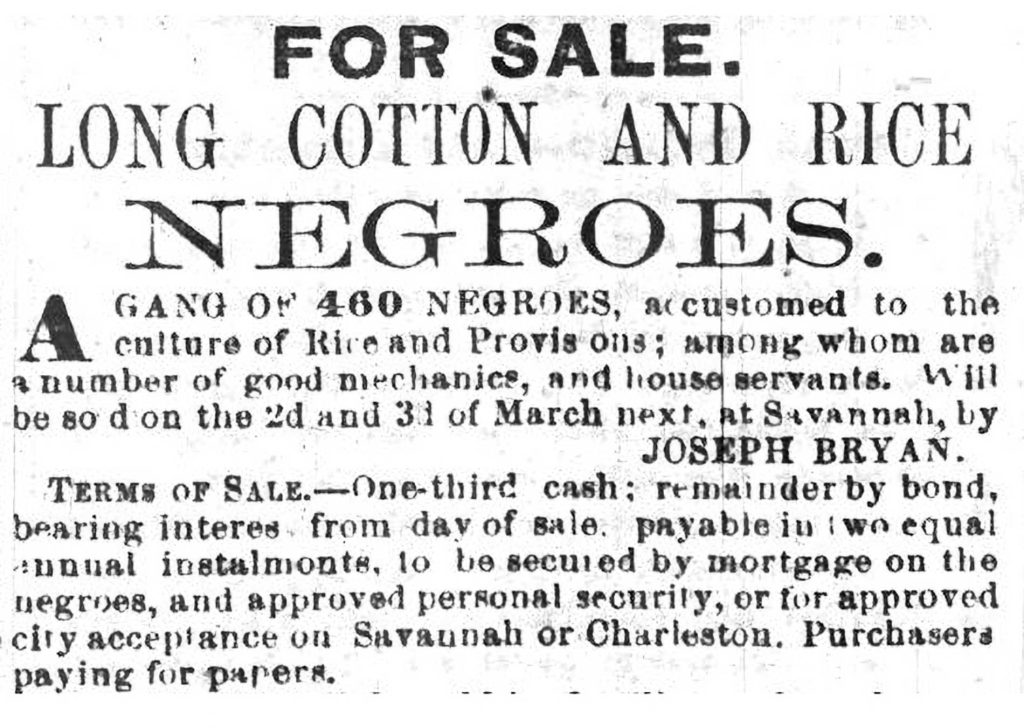

- “The Weeping Time”

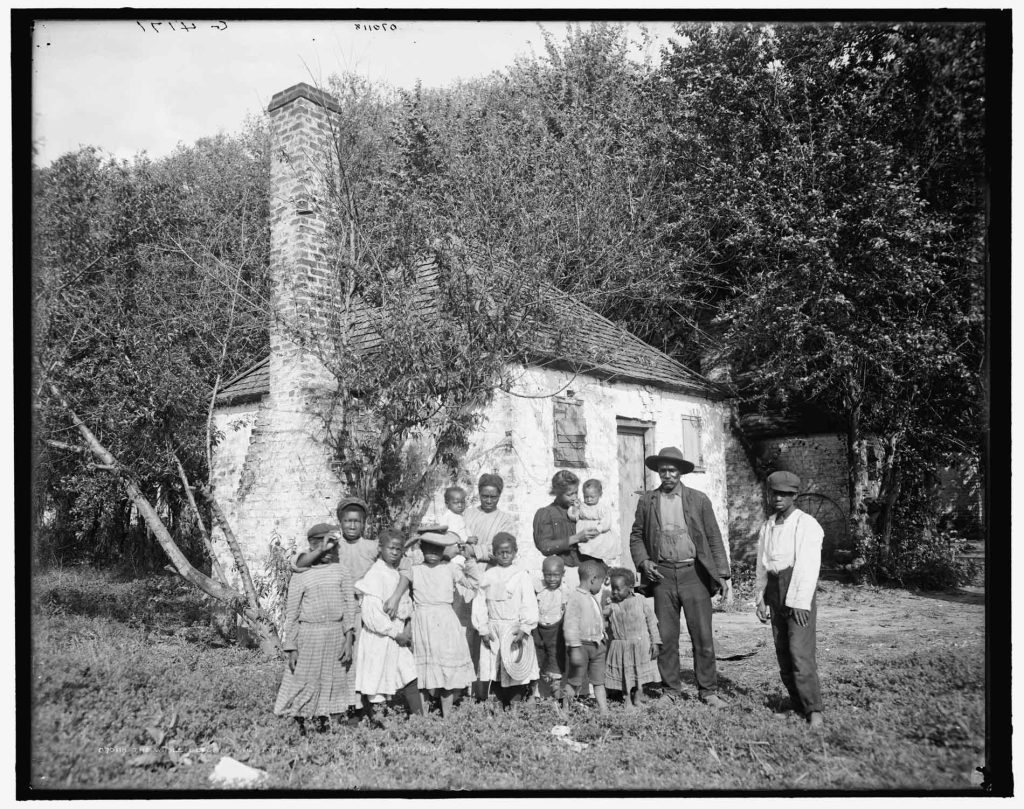

- Legacy of Enslavement

- A City Built on Trafficking

- Brutal Conditions

- Resistance and Violent Response

Chapter 1

Origins

In this Chapter

- The European Influence on Africa

- The Barbarity of the Middle Passage

- Slavery in the Americas

The enslavement of people has been a part of human history for centuries. Slavery and human bondage has taken many forms, including enslaving people as prisoners of war or due to their beliefs,1 but the permanent, hereditary enslavement based on race later adopted in the U.S. was rare before the 15th century.

Many attributes of slavery began to change when European settlers intent on colonizing the Americas used violence and military power to compel forced labor from enslaved people. Indigenous people became the first victims of forced labor and enslavement at the hands of Europeans in the Americas. However, millions of Indigenous people died from disease, famine, war, and harsh labor conditions in the decades that followed.2

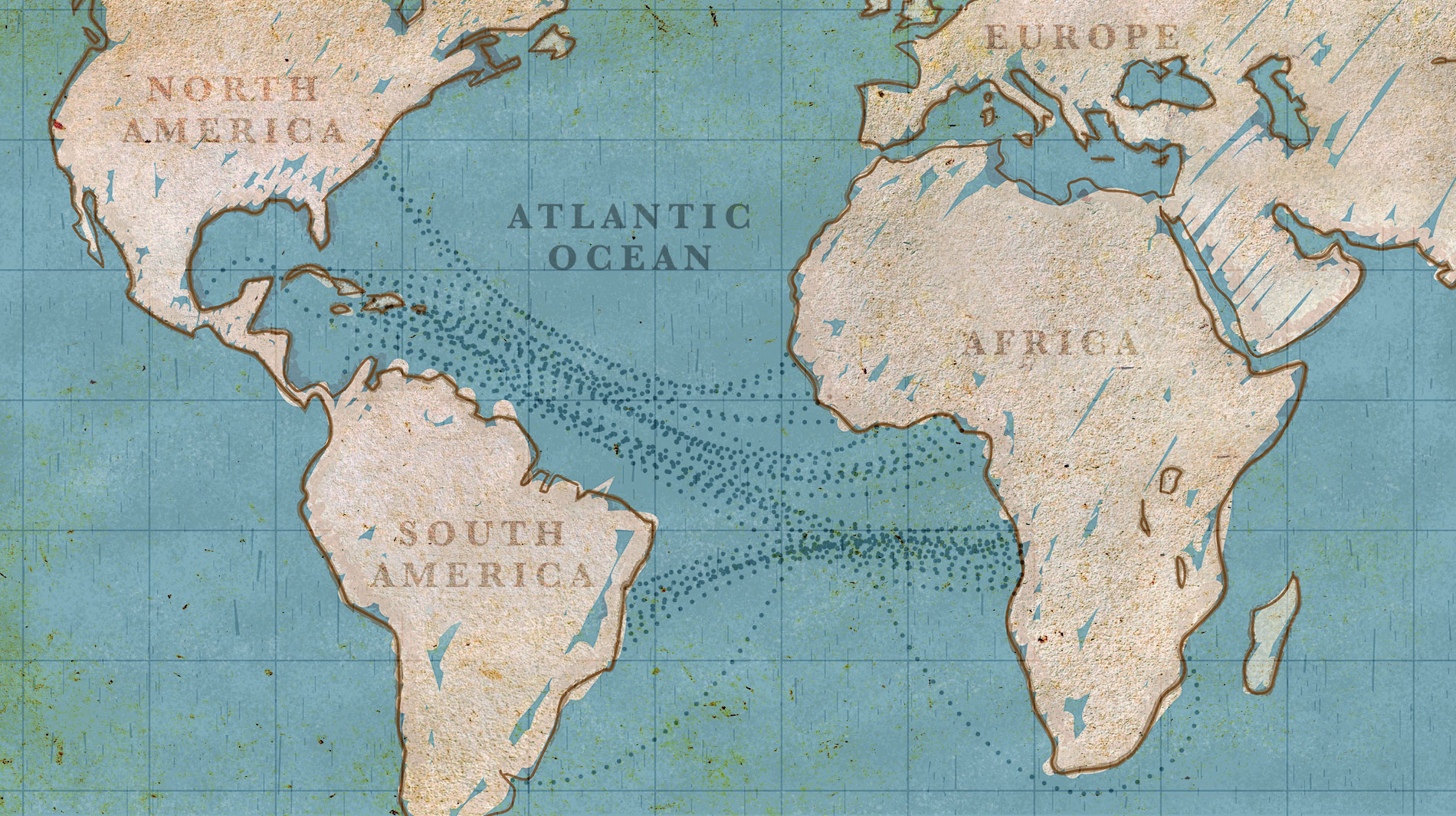

Committed to extracting profit from their colonies in the Americas, European powers turned to the African continent. To meet their ever-growing need for labor, they initiated a massive global undertaking that relied on abduction, human trafficking, and racializing enslavement at a scale without precedent in human history. Never before had millions of people been kidnapped and trafficked over such a great distance.

The permanent displacement of 12.5 million African people to a foreign land, with no possibility of ever returning, created an enduring legacy and shaped challenges that remain with us today.3

The European Influence on Africa

Europe had no contact with Sub-Saharan Africa before the Portuguese, seeking wealth and gold, sailed down the western coast of Africa and reached the Gold Coast (modern-day Ghana) in 1471.4 Initially focused on obtaining gold, Portugal established trading relationships and built El Mina Fort to protect its interests in the gold trade.5

The convergence of European powers in Sub-Saharan Africa set in motion a devastating process that fused sophisticated labor exploitation, international commerce, mass enslavement, and an elaborate race-based ideology to create the Transatlantic Slave Trade.6

Over the following decades, the Spanish, English, French, Dutch, Danish, and Swedes began to make contact with Sub-Saharan Africa as well. Portugal soon converted El Mina into a prison for holding kidnapped Africans, and European traffickers built castles, barracoons, and forts on the African coast to support the forced enslavement of abducted Africans.

German and Italian merchants and bankers who did not personally traffic kidnapped Africans nonetheless provided essential funding and insurance to develop the Transatlantic Slave Trade and plantation economy.7 Italian merchants were essential in the effort to extend the sugar plantation system to the Atlantic Islands off the west coast of Africa, like São Tomé, and financial capital from Genoa was instrumental in expanding Portugal’s ability to traffic Africans.8

By the 1600s, every major European power had established trading relationships with Sub-Saharan Africa and was participating in the transportation of kidnapped Africans to the Americas in some way. During this time period, several thousand Africans were kidnapped and trafficked to mainland Europe and the Americas, but the volume of human trafficking soon escalated to horrific proportions.9

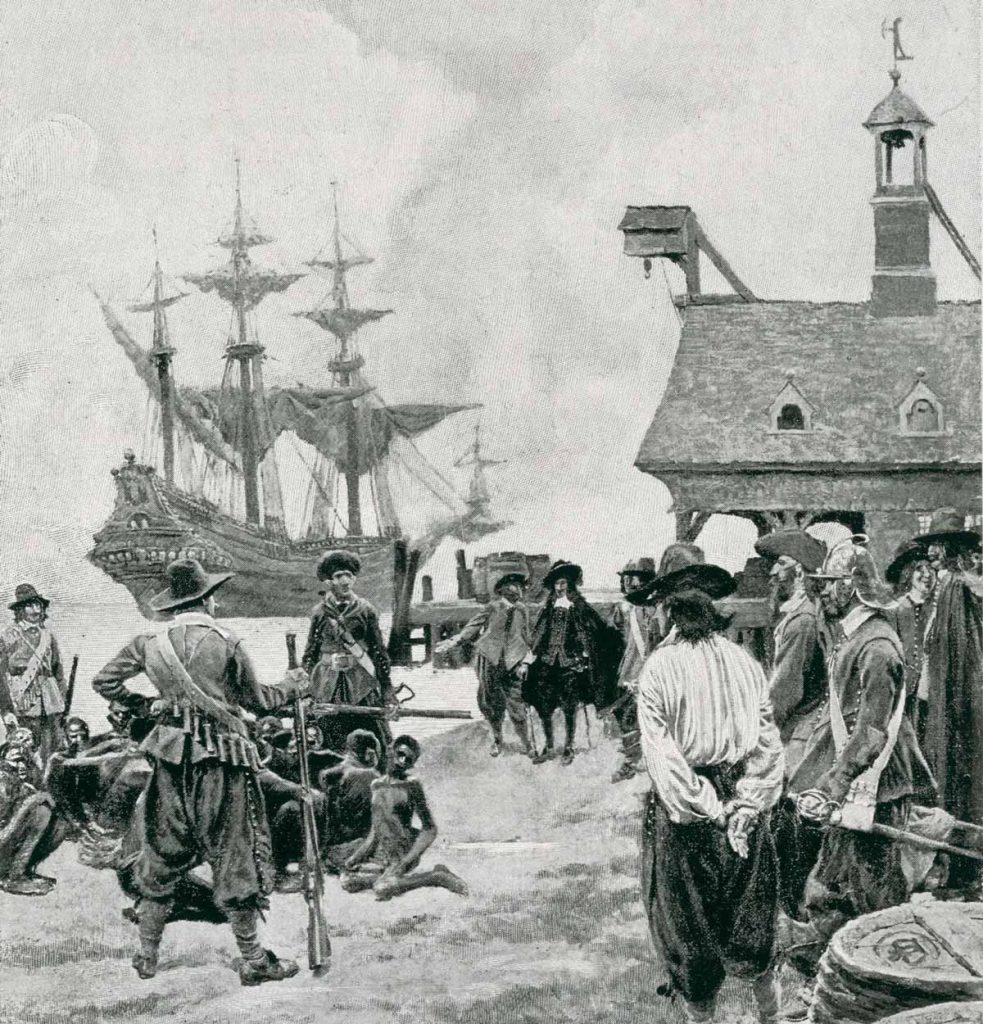

An engraving of trafficked Africans arriving in Virginia in 1619.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Led again by the Portuguese, European powers began to occupy the Americas in the 1500s. In the 16th and 17th centuries, using land stolen from Indigenous populations in the Americas, Europeans established plantations that relied on enslaved labor to mass produce goods (primarily sugar cane) for trading and sale.10 The cultivation of sugar for mass consumption became a driving force in the growing trafficking of human beings from Africa.11

Europeans initially relied on Indigenous people to supply this labor.12 But mass killings and disease decimated Indigenous populations in what historian David Brion Davis called “the greatest known population loss in human history.”13

The Indigenous population in Mexico plummeted by nearly 90% in 75 years. In Hispaniola (modern-day Haiti and Dominican Republic), the population of Arawak and Taino people fell from between 300,000 and 500,000 in 1492 to fewer than 500 people by 1542, just five decades later.14 Without Indigenous workers, plantation owners in the Americas grew desperate for a new source of exploited labor.15

Driven by the desire for wealth, these European powers shifted from acquiring gold and other goods in Sub-Saharan Africa to trafficking in human beings. Over the following centuries, Europeans demanded that millions of Africans be trafficked to work on plantations and in other businesses in the Americas.16

Slavery had existed in Africa prior to this point, but this new commodification of human beings by European powers was entirely unique and it drastically changed the African concept of enslavement.17

Although some African officials and merchants acquired wealth through the export of millions of people, the Transatlantic Slave Trade devastated and de-stabilized societies and economies across Africa. The scale of disruption and violence contributed to long-term conflict and violence on the continent while European powers were able to amass massive financial benefits and global power from this dehumanizing trade.18

The Iberian powers of Spain and Portugal and their colonies in Uruguay and Brazil were responsible for trafficking 99% of the nearly 630,000 kidnapped Africans trafficked from 1501 to 1625.19 Over the next 240 years, England, France, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, the Baltic States, and their colonies joined the Iberians in actively trafficking Africans. Almost 12 million kidnapped Africans were trafficked from 1625 to 1867.20 Ships from Portugal and its colony Brazil alone were responsible for trafficking 5,849,300 kidnapped Africans during this time period.21

Ships originating in Great Britain were responsible for trafficking more than a quarter of all people taken from Africa from 1501 to 1867.22 From 1726 to 1800, British ships were the leading traffickers of kidnapped Africans, responsible for taking more than two million people from Africa.23

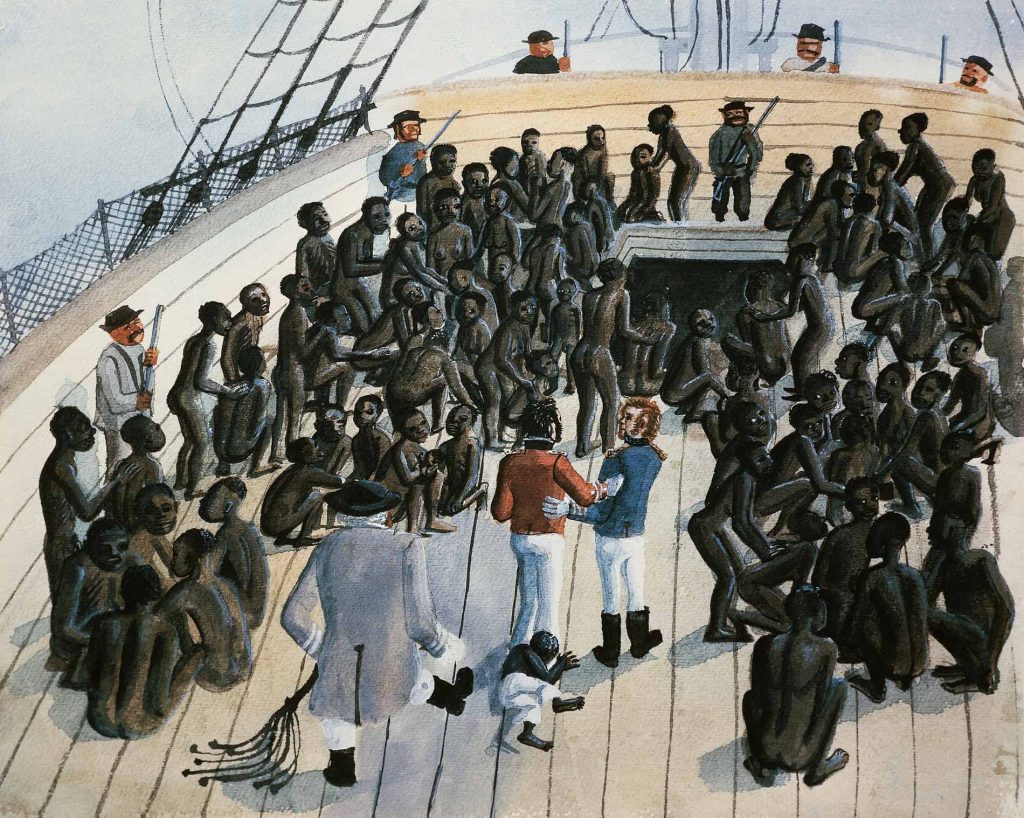

A painting of kidnapped Africans aboard a trafficking ship.

Dea/G. Dagli Orti/Getty Images

From 1626 to 1867, ships from North America were responsible for trafficking at least 305,000 captured people from Africa. In the two years before the U.S. legally ended the international slave trade in 1808, a quarter of all trafficked Africans were carried in ships that flew the U.S. flag.24 Rhode Island’s ports combined to organize voyages responsible for trafficking at least 111,000 kidnapped Africans, making it one of the 15 largest originating ports in the world.25

The Barbarity of the Middle Passage

The horrific conditions of the Middle Passage meant that of more than 12.5 million Africans kidnapped and trafficked through the Transatlantic Slave Trade, only 10.7 million survived the journey.26

Eighty percent of the people who embarked for the Americas between 1500 and 1820 were kidnapped Africans, who far outnumbered European immigrants.27

Almost two million Africans died during the Middle Passage—nearly one million more than all of the Americans who have died in every war fought since 1775 combined.28

Numbers like this can help to quantify the scope of the harm, but they fail to detail the horrific and torturous experience of those who perished and the trauma that 10.7 million Africans who survived the weeks-long journey carried with them.

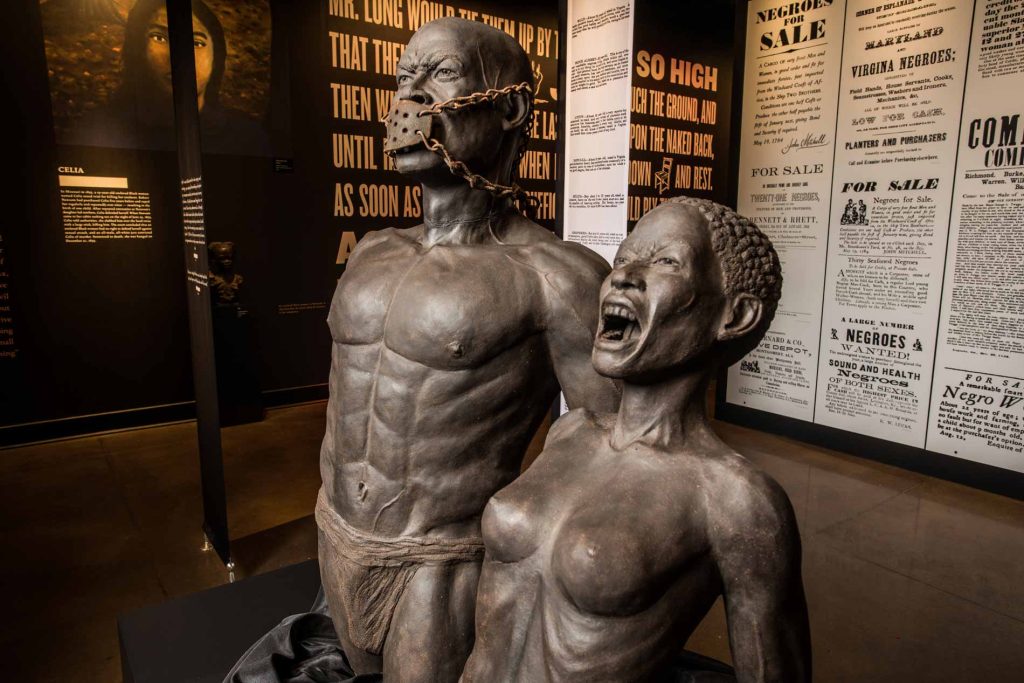

An exhibit at EJI’s Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, features more than 200 sculptures by Ghanaian sculptor Kwame Akoto-Bamfo memorializing those who died during the Middle Passage.

Human Pictures

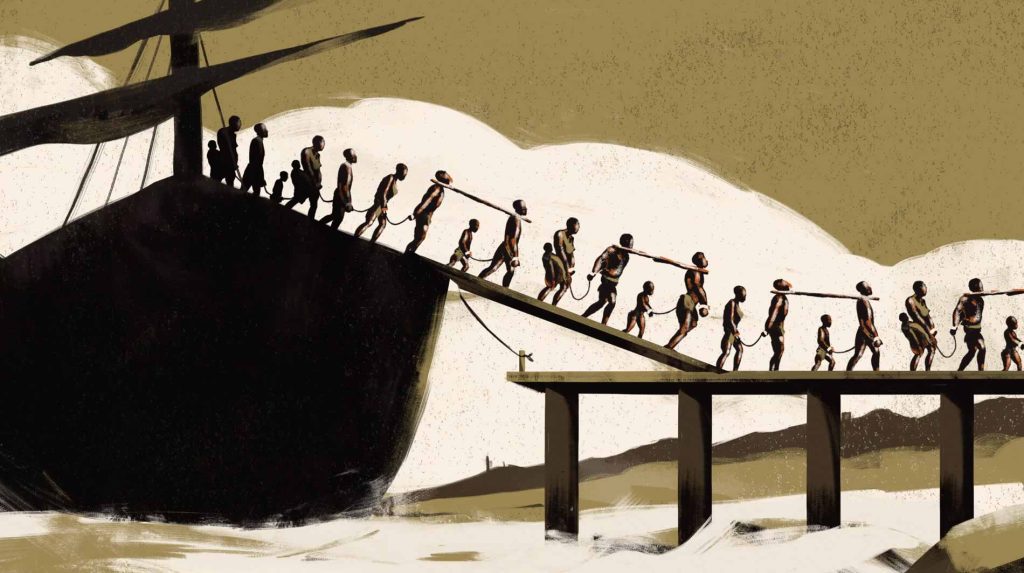

Some enslaved people were taken from the coast of West Africa and sold to European slave traders. For most captives the experience of Transatlantic trafficking began weeks, months, or even years before they ever saw the coast. Driven by the increasing external demand from white enslavers and traders, African kidnappers traveled inland and kidnapped people from their villages and towns. In the 18th century, 70% of Africans trafficked in the Transatlantic Slave Trade were free people who had been “snatched from their homes and communities.”29 They were most often forced to walk, bound together in a coffle, for dozens or even hundreds of miles until they reached the coast.30

At the coast, kidnapped Africans were forced into barracoons, slave pens, and dungeons within prison castles to await the ships that would take them across the Atlantic. Kidnapped Africans were forced to board slave trading ships that stayed docked—sometimes for months—until they had loaded enough human cargo to make the passage sufficiently profitable for the enslavers.31 Records do not establish an exact death toll, but scholars estimate the mortality rate among those confined in barracoons and on board docked trading ships “equaled that of Europe’s fourteenth-century Black Death,” which claimed at least 40% of Europe’s population.32

Countless Africans perished before they even began the Middle Passage.33

Ottobah Cugoano was a young child when he was “snatched away from [his] native country, with about eighteen or twenty more boys and girls.”34 The kidnappers brandished “pistols and cutlasses” and threatened to kill the children if they did not come with them.35 For Ottobah and millions like him, the trauma of familial separation would be inflicted repeatedly in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Ottobah’s “hopes of returning home again were all over”36 as he was marched to the coast and placed in a prison until a white slave trader’s ship arrived three days later. “[I]t was a most horrible scene,” Ottobah later recounted.37

“[T]here was nothing to be heard but the rattling of chains, smacking of whips, and the groans and cries of our fellow-men. Some would not stir from the ground, when they were lashed and beat in the most horrible manner.”

Ottobah Cugoano

“Narrative of the Enslavement of Ottobah Cugoano,” 124.

African captives were forced to undergo invasive and dehumanizing examinations before they boarded enslavers’ ships. Women, men, and children were stripped naked, prodded, and molested to determine if they were “prime slaves” capable of performing hard labor and having children.38

Traders invasively groped the breasts, buttocks, and vaginal areas of women and young girls, allegedly to assess their childbearing ability.39 Men and boys were similarly molested around the groin, scrotum, and anus.40 One white trafficker later testified the process was similar to what he would do to “a horse in this country, if I was about to purchase him.”41

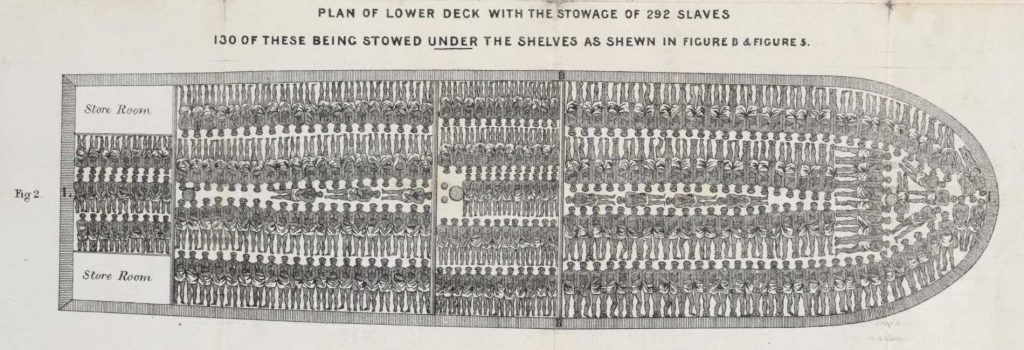

Captives were then assigned a number and loaded onto ships, separated by gender and tightly packed into the holds under conditions that were noxious and extreme. Men were typically “locked spoonways” together, naked and forced to lie in urine, feces, blood, and mucus, with little to no fresh air.42 Alexander Falconbridge, a white surgeon who participated in the slave trade, later testified that captives “had not so much room as a man in his coffin, neither in length or breadth, and it was impossible for them to turn or shift with any degree or ease.”43

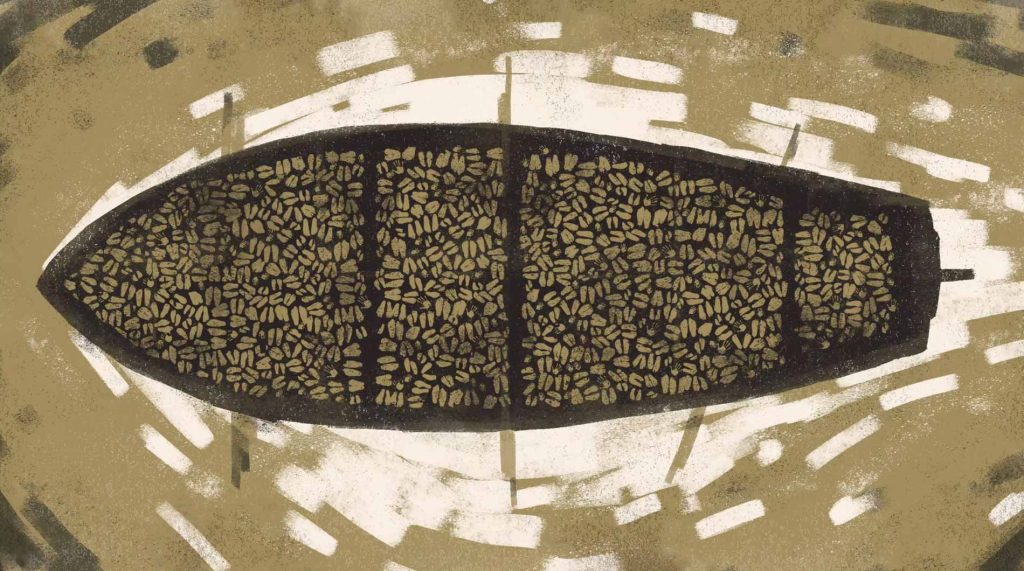

An illustration of the Brookes, a British ship used to traffic enslaved people.

Library of Congress

Trafficked Africans were forced to lie chained and manacled for weeks during the journey, unable to stretch out or stand except during limited time on deck. The foul conditions were a breeding ground for disease and vermin; some captives suffocated from the lack of air below deck.44 On some ships, the mortality rate was as high as 33%.45

About 15% of kidnapped Africans—nearly two million people—died during the Middle Passage.

African women and girls suffered similarly horrific conditions in the hold—and they were uniquely terrorized by the crew. Forced to be naked and segregated from the men, they lived in constant fear of being raped or assaulted by white sailors, who subjected them to sexual violence and flogged those who resisted.46

Sexual assault of African women was so commonplace that Alexander Falconbridge later testified that sailors were “permitted to indulge their passions among them at pleasure.”47 Young girls were similarly subjected to violence. One surviving account details the experience of “a little girl of eight to ten years” who was repeatedly raped by a ship’s captain over three consecutive nights.48

White sailors engaged in sexual violence without any fear of consequences or accountability.49

Some African women faced a second level of terror—the inability to protect their small children who were brought on board with them or born during the voyage.50 Many African women were forcibly separated from their infants when they were kidnapped from their homes or when they were sold to white traffickers but some women carried small infants with them. Babies were of little value in the market across the Atlantic, and so abusive sailors used them to manipulate, control, and terrorize their mothers.51 One account details a sailor who “tore the child from the mother, and threw it into the sea” when the newborn would not stop crying.52

Enslaved women and young girls were systematically subjected to sexual abuse and violence by traffickers and enslavers.

Library of Congress

Another account from a white trafficker reports that a woman and her nine-month-old were purchased and placed onboard a ship. The baby “would not eat,” so the captain “flogged him with a cat o’ nine tails” in front of his mother and other captives on the ship.53 When he noticed that the baby’s feet were swollen, the captain ordered his crew to submerge the baby’s legs in boiling water, causing “the skin and nails [to come] off.”54 The baby still would not eat, so the captain flogged him at each meal time for several days before finally “[tying] a log of mango, either eighteen or twenty inches long, and about twelve or thirteen pound weight, to the child by a string round its neck,” beating the baby again, and dropping the baby to the ground, killing him.55 His mother—powerless to save her baby—was beaten until she agreed to throw her baby’s body overboard. This act of terror was intentionally committed in view of other captives to strike fear and maintain control.56

Cruelty and terrorism were common on trafficking vessels operated by Europeans. Sailors inflicted brutal punishments for even minor offenses as a reminder of their control.57 One account from a white sailor reported that eight to 10 captives were brought to the top deck one night “for making a little noise in the rooms.”58 Sailors were then ordered to “tie them up to the booms [horizontal poles extending from the base of the mast], flog them very severely with a wire cat [a whip with multiple tails of wire], and afterwards clap the thumb-screws upon them, and leave them in that situation till morning.”59 The same sailor said the use of the thumb-screws—a device that crushed fingers via pressure—was so violent and harmful that it resulted in “fevers” and even death on occasion.60

For more serious offenses, sailors inflicted even greater violence. One captive woman who was accused of aiding (but not actively participating) in an attempted revolt against the kidnappers, was strung up on the deck by her thumbs in view of the other captives. As a warning to them, she was flogged and knifed to death.61

An illustration published in an 1833 anti-slavery periodical shows traffickers throwing enslaved people overboard.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The threat of being flogged with a cat o’ nine tails [a multi-tailed whip with lashes often tipped with metal or barbs] or placed in the thumb-screws hung over each captive.62Consuming more than their meager allotment of food could lead to whipping and torture.63 Captives were forced onto the deck and made to “dance” for exercise under threat of flogging. As one eyewitness observed, “Even those who had the flux, scurvy, and such edematous swelling in their legs, as made it painful to them to move at all, were compelled to dance by the cat.”64 Failure to eat one’s rations likewise resulted in abuse, whipping, or torture in the thumb-screws until the kidnapped African agreed to eat.65

These excruciating conditions lasted for weeks and sometimes for months. A typical voyage took five or six weeks; some took two or three months.66 Longer voyages led to higher mortality rates among the kidnapped Africans on board.67

When the ships landed in ports across North and South America, the kidnapped Africans who survived the Middle Passage were subjected to a renewed round of examinations and molestation by enslavers before they were sold again and forced to do hard labor that often resulted in their untimely deaths.68 Around 80% of kidnapped Africans transported across the Middle Passage were forced to work on sugar plantations under incredibly dangerous conditions that led to high mortality rates.69

Sidebar

Olaudah Equiano

Read More

Slavery in the Americas

Of the enslaved men, women, and children who survived the Middle Passage, approximately 90% arrived in the Caribbean or South America.82 The Portuguese, Spanish, French, British, and Dutch controlled slavery in the Americas, and each followed different political, legal, and cultural practices.83 Due in part to these differences, the evolution of slavery in the Americas varied across the region, as did the social construction of race and racial hierarchy.

There is no value in comparing the relative “harshness” of slavery across the Americas; the brutality and inhumanity of slavery was universal. Moreover, conditions in the South American and Caribbean colonies were horrific—the vast majority of enslaved people in these colonies worked on sugar plantations, which were notoriously harsh environments. Work on these plantations was “life-consuming,” with long hours of gang labor—often beginning at 5 a.m. and working until dusk—and extremely hazardous work conditions. Plantations in Brazil had higher mortality rates and lower life expectancies than plantations in the U.S.84

Factors specific to each European power and its colonies distinguished the experiences of enslaved men and women across the Americas. In the North American colonies and later the U.S., white people were in the majority everywhere except in South Carolina and Mississippi.85 But in South America and the Caribbean, nonwhite people regularly exceeded 80% of the population.86

When the Haitian revolution started in August 1791, white Europeans made up just 7% of the population and there were roughly as many free people of color as there were Europeans.87 Iberian control in South America was challenged by the growing number of enslaved people, who often demanded their freedom in exchange for fighting Indigenous people who resisted European colonizers.88 In these colonies, the threat of rebellion against the minority white population was critical in shaping society.

In contrast, the exceptionally large white majority in North America meant that rebellions by enslaved people, while far more common than most people realize today, did not represent as great a threat to white rule.89 As a result, while the fear of rebellions profoundly shaped the legal and cultural landscape of North America,90 British colonists rarely were forced to make legal or political concessions to enslaved people.

Geographic and demographic variations also distinguished how race and racial hierarchy developed in North America. For example, during the first century of Portuguese colonization in Brazil, there were very few Portuguese or white women,91 which meant that despite anti-miscegenation laws passed in Portugal, there were high rates of interracial sex between white men and women of African descent in Brazil.92 By 1822, more than 70% of Brazil’s population “consisted of blacks or mulattoes, slaves, liberto, and free” people of color.93

Today, Brazil is home to the largest population of African descendants outside the African continent.94

In most South American and Caribbean colonies, large populations of free people of color emerged and “elaborate human taxonomies” based on race and caste were developed.95 A different racial hierarchy evolved in North America, where free people of color represented a very small fraction of the population.96 There, a single, rigid color line separated two racial groups: Black and white.97

Finally, the legal codes that governed enslaved peoples’ lives—laws on manumission, the status of enslaved people as humans or property, marriage and family formation, and racial classification—varied by region and the colony.98 These laws demonstrate the complex racial hierarchies in the region.

Throughout the region, racial discrimination was codified in laws that barred free Black people from “hold[ing] political office, practic[ing] prestigious professions (public notary, lawyer, surgeon, pharmacist, smelter) or enjoy[ing] equal social status with whites.”99 But in 1795, the Spanish Crown made it possible to purchase whiteness—people of color with mixed ancestry could “apply and pay for a decree” that converted their legal status to white.100 These laws sparked “vigorous and serious debate concerning the civil rights of those of mixed descent” in some countries. The 1812 constitution of the Spanish Empire further expanded opportunities for mixed-race citizens, including desegregating universities a century and a half before the U.S.101

In French colonies, the “Code Noir” passed by Louis XIV in 1685 shaped an entirely different landscape. The code mandated execution for an enslaved person who struck their enslaver,102 but it also granted free people of color the same rights as any “persons born free,”103 prohibited enslaved parents from being sold separately from their children,104 deemed free the child of a free woman and an enslaved man of color,105 and fined an enslaver who had a child with an enslaved woman unless he married and freed the woman and her child.106

Critically, under the Code Noir, free people of color dramatically increased their numbers. In Louisiana, which spent decades under French control, there were 18,647 free Black people by 1860—almost 3,000 more than in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi combined.107

The British and their descendants in North America made race the central aspect of laws governing slavery and the lives of enslaved and free Black Americans.108 A stark “black-white binary” reflected and reinforced the centrality of race in all areas of American life.109

As a result, while the particular experience of slavery depended on region and time period, enslavement in the U.S. became a rigid, racialized caste system that inexorably tied enslavement to race.

The system of enslavement that emerged in North America was legitimated by an elaborate set of laws enforced through terror and violence and used to justify and codify the permanent, hereditary, and unending slavery of Black people for generations.

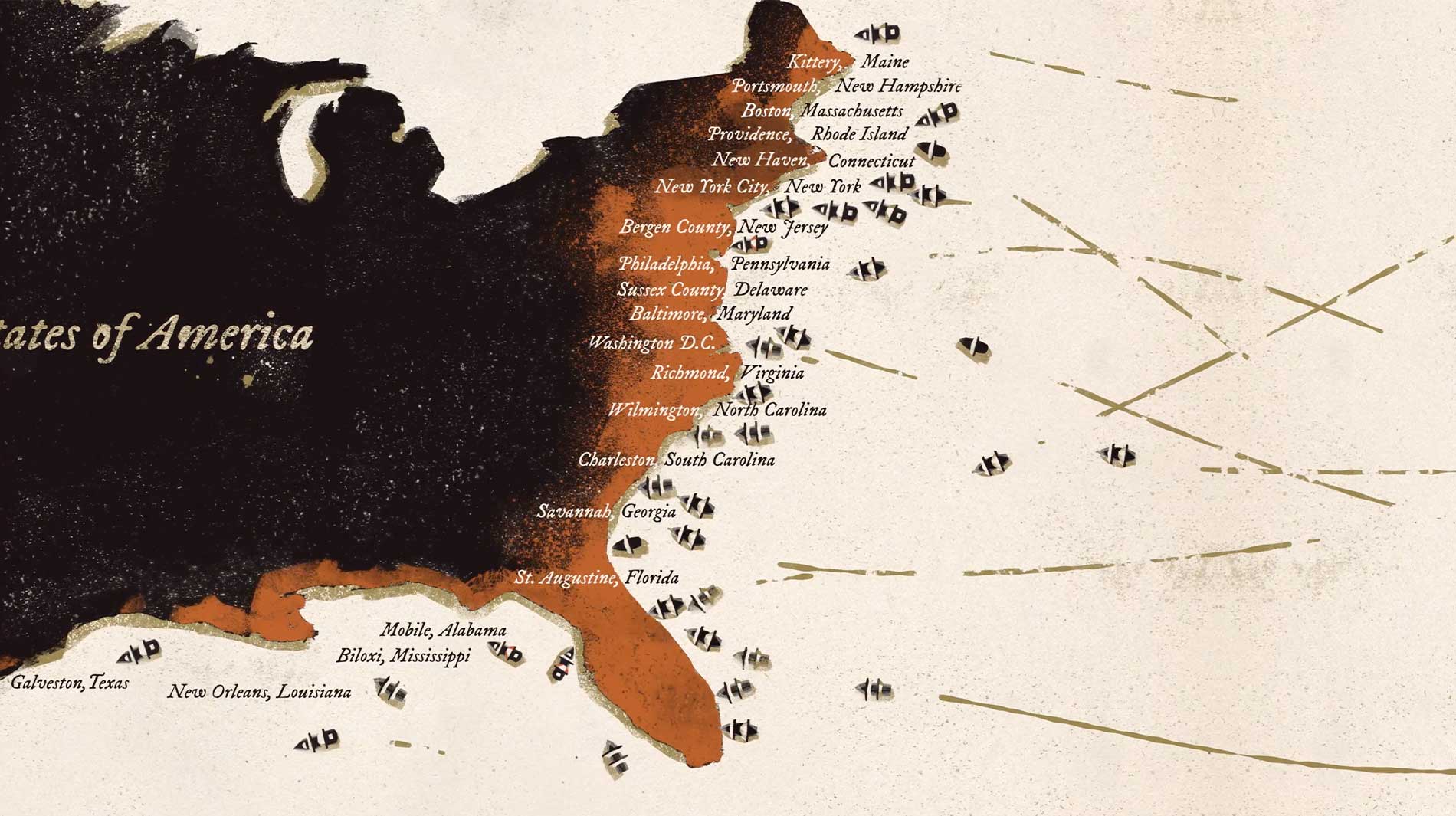

From the first arrival of kidnapped Africans in the English colonies that would become the United States, the institution of enslavement was foundational to the economy of every major city on the Eastern Seaboard. The history of these regions cannot be fully understood without acknowledging the role enslavement played in creating their economies, laws, and political and cultural institutions and the innumerable ways this legacy shapes these communities today.

Sidebar

The Role of the Christian Church

Read More

Chapter 2

New England

In this Chapter

- New England Trafficking

- A Trafficking-Based Economy

- Industries Reliant on Enslaved Labor

- Laws Limiting Freedom

By 1638, English colonizers in New England had killed or enslaved more than 1,500 Pequot men, women, and children.120 Pequot Indians who survived were forced to work in New England or were shipped to the West Indies and exchanged for kidnapped Africans, marking New England’s first involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade.121

Recognizing the enormous wealth that could be gained from trafficking enslaved people, colonists began trafficking kidnapped African men, women, and children to Massachusetts (which included present-day Maine) as early as 1638,122 to Rhode Island after 1638, to New Hampshire by 1645,123 and to Connecticut by 1660.124

In 1641, Massachusetts became the first North American colony to formally legalize slavery.125 By 1670, the enslavement of Black people in Massachusetts was codified as a hereditary and permanent legal status—a model later adopted by other New England colonies.126

Whole regional economies were built around the slave trade, generating enormous wealth for generations of white New Englanders, who established a narrative of racial difference that deemed Black people subhuman.127 Even after some called for abolition of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and steps were taken toward “gradual emancipation,” white New Englanders remained committed to the system of slavery that sustained their local, regional, and international economies. Enslavement remained legal in parts of New England well into the 1840s.128

New England’s burgeoning economy revolved around the Transatlantic Slave Trade, as each industry—from rum production and fisheries to produce and shipbuilding, and later, insurance and manufacturing—was fueled by human trafficking.

Every colony in New England produced and shipped goods to plantations in the West Indies in exchange for more abducted Africans.129 Connecticut merchants sold cattle, codfish, onions, wheat, and potatoes to Caribbean plantation owners,130 while Maine, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island merchants exported fish to the Caribbean as part of a global trade that sustained plantation life and generated enormous profits for white colonists.131

New England Trafficking

As the Transatlantic Slave Trade grew into a massive international enterprise, New England docks became increasingly crucial for traffickers. At least 314 trafficking voyages carrying nearly 45,000 kidnapped Africans landed or ended in New England ports between 1678 to 1807, and at least 5,000 Africans kidnapped and trafficked in those voyages were enslaved in New England.132

New England ports were also the originating points of Transatlantic voyages. From 1645 until 1860, at least 1,170 ships departed from New England en route to Africa, where at least 148,659 kidnapped African women, men, and children were packed into their cargo holds.133

New Englanders profited from the kidnapping and trafficking of African people around the world.134

The business of buying and selling Black people was not limited to large firms, but was pervasive among New England business owners, who purchased shares in Transatlantic voyages.135

In Rhode Island alone, at least 700 individuals owned or captained ships carrying enslaved people.136 Indeed, about half of all voyages originating in North America departed from ports in Rhode Island, making it the most prominent organizing port in North America and one of the top 15 in the world.137 More than half of these Rhode Island ships sold enslaved people in the Caribbean; the rest sold enslaved people in South Carolina and other North American markets.138

A sculpture by Ghanaian sculptor Kwame Akoto-Bamfo at the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama.

Bryan G. Stevenson

Transatlantic voyages ending in New England were long, tortuous journeys that often resulted in death. From 1678 to 1807, at least 5,700 kidnapped Africans died on voyages that ended in New England.139

During a 1719 voyage leaving Antigua and destined for Kittery, Maine, four of the five kidnapped Africans aboard died, possibly due to insufficient clothing during cold spring months. The sole surviving woman died three weeks later.140

In 1789, on The Polly, a Rhode Island-based ship bound for Havana from present-day Ghana, human trafficker James D’Wolf murdered an enslaved woman who he believed had smallpox by blindfolding her, tying her to a chair, and throwing her overboard.141According to his crew, he “lamented only the lost chair.”142 D’Wolf went on to serve in the Senate.143

A group of enslaved people, nearly starved to death, who were rescued from a trafficking ship.

The National Archives of the UK: ref. F084/1310

A Trafficking-Based Economy

As the Transatlantic Slave Trade grew, the buying and selling of kidnapped Africans—and the exploitation of their labor—formed the backbone of a growing New England economy.

In what became known as the “Triangle Trade,”144 New England traders imported sugar and molasses produced by enslaved people on Caribbean plantations and manufactured rum that they shipped to West Africa, where it was exchanged for enslaved Africans, who were sold to Caribbean plantations for more sugar.145 Rhode Island and Massachusetts built the largest distilleries in the colonies. Rum production became New England’s biggest manufacturing business until the American Revolution.146

New England politicians harnessed the enormous profits from trafficking enslaved people for state-building projects.

Massachusetts and Rhode Island built infrastructure that remains today with tax revenue collected from traffickers for each person they kidnapped and brought to the colonies through 1732.147 New Hampshire and other colonies declined to impose taxes on traffickers in order to lure more ships to their ports, resulting in growing trade, the exploitation of more Black labor, and the development of regional wealth.148

Kidnapped Africans who survived the journey to New England were sold into slavery at auctions on board the ships in which they were trafficked, in private homes, taverns, and public meeting houses.149

The lucrative buying and selling of kidnapped Africans, supported by a legal architecture that made slavery hereditary and permanent, allowed enslavement to flourish.

Some enslaved African people learned highly skilled trades, but were allowed no choice over when to utilize their valuable knowledge and were prevented from earning money to support themselves or their families.150

A sculpture by Kwame Akoto-Bamfo at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

Human Pictures

Family separation was common in New England, despite Puritan family values. A Massachusetts newspaper in 1782 advertised a 19-year-old enslaved Black woman and her six-month-old baby for sale either “together or apart.”151 Enslaved people in New England were often made to live in the homes of their enslavers and work alongside their enslavers in local industries where they were under constant surveillance.152

By the start of the Revolutionary War, one in four estates in Connecticut enslaved at least one Black person.153

Despite widespread narratives advanced by New Englanders who claimed their type of slavery was based on the belief that “slaves were considered part of their [enslaver’s] family,” racial hierarchy and violence were dominating features of enslavement in New England.154

A Connecticut newspaper in 1774 advertised the sale of a 14-year-old “Negro Boy” who “has one of his little toes cut off, and a dent in his forehead.”155 In New Hampshire, an advertisement read: “Ran-away…a NEGRO Servant named Neptune, of about 25 Years of age…his under Jaw has been broken, so that he can’t open his Jaws; and one of his great Toes has been cut off.”156

Industries Reliant on Enslaved Labor

In the 1800s, New Englanders found new ways to profit from the exploited labor of enslaved people, including a textile industry that relied on cotton harvested by enslaved labor on plantations in the American South and the West Indies.157 Nearly 300 textile mills opened in Rhode Island between 1790 and 1860.158

By 1860, 67% of the cotton milled in the U.S. was milled in New England, and Massachusetts mills operated 30% of the spindles in use at the time.159

Connecticut dominated New England’s insurance industry, which insured human property for enslavers around the country until the 1850s. Insurance companies based in Newport, Hartford, and New London issued policies to enslavers and shipowners that promised to pay enslavers hundreds of dollars for each enslaved person who died onboard or while performing grueling labor.160

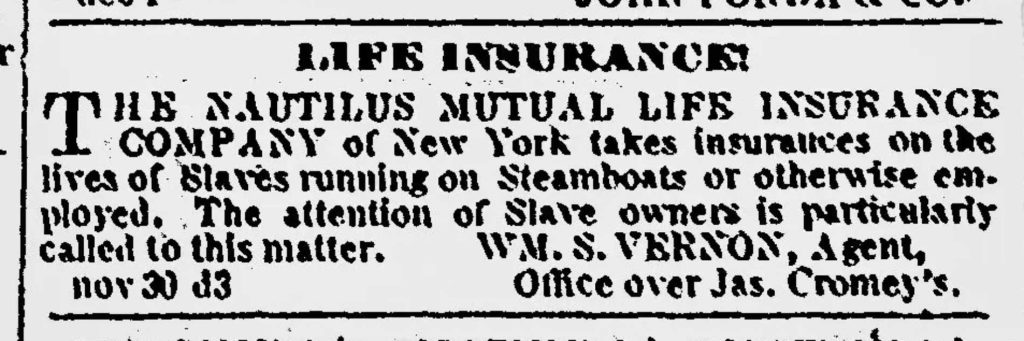

An 1847 ad placed by Nautilus Mutual Life Insurance (later renamed New York Life Insurance) offering insurance policies on enslaved people.”

The Daily Democrat

This financial scheme incentivized the killing of Black people. In 1781, shipowners murdered 133 kidnapped Africans by throwing them overboard the Zong so they could collect the insurance.161

From their founding, companies like Charter Oak Life Insurance Company, New York Life (called Nautilus Insurance Company in the 1840s), and Aetna Inc. in Connecticut profited from the slave trade by selling policies to traffickers.162

Laws Limiting Freedom

Some New Englanders called for the “gradual emancipation” of enslaved people, passing laws that freed no one immediately while still preserving the racial hierarchy.163Under Connecticut’s Gradual Emancipation Act of 1784, enslaved people remained enslaved for life, while their children and grandchildren remained enslaved until their 20s.164 It was not until 1848 that Connecticut formally abolished slavery.165

There were also calls for abolition of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in the late 18th century, but legislation limiting the slave trade was largely ignored and perpetrators were rarely convicted.166

Federal laws passed in 1794 and 1800 barred citizens from “owning, outfitting, investing in, or serving aboard ships” that carried enslaved people to ports outside the U.S.—and white New Englanders violated them both.167

Nearly half of enslaved people transported to Rhode Island were trafficked illegally in violation of state and federal statutes, but most of the 22 illegal trafficking cases prosecuted in Rhode Island ended in acquittal.168

Thus, trafficking of enslaved people in New England continued even after Congress formally abolished the Transatlantic Slave Trade in 1807.169

A sculpture from Memory of Slaves, a monument to enslaved people in Stone Town on the island of Zanzibar in Tanzania.

Elena Niccolai

All the while, racial terror dominated.

Free Black people in New England were subjected to curfews, discrimination, Black Codes, bans on interracial marriage, and frequent violence from white citizens.170

In 1824, white community members in Providence, Rhode Island, destroyed nearly every home and business in a Black neighborhood after a group of Black residents failed to step off the sidewalk to let a group of white people pass.171

The narrative of racial difference that justified the trafficking of Black people that propagated the growth of New England industries persisted long after New Englanders joined their fellow colonists to declare that “all men are created equal.” Indeed, white New Englanders remained committed to white supremacy long after the abolition of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the end of slavery in the U.S.172

Chapter 3

Boston, Massachusetts

In this Chapter

- The Port of Boston

- Controlling Enslaved People

- Profiting from Trafficking

- After Abolition

Massachusetts was the first colony in New England to formally authorize the enslavement of kidnapped Africans and slavery remained legal for over 140 years before it was gradually abolished in 1783.173

Boston’s wealthy white elite were at the center of the lucrative enslavement-based economy, directly enslaving Black people and profiting from Boston’s role in the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Boston traders, investors, and businesspeople were responsible for at least 307 separate trafficking voyages. Boston served both as the origin port for outbound ships en route to the coast of Africa to capture and kidnap woman, men, and children and as a final trafficking destination for the sale of enslaved Africans.174

Watch: Boston was a major port in the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

The Port of Boston

In 1638, Boston’s first documented trafficking ship departed from Boston for Bermuda.175 Enslavers aboard the Boston-built Desire trafficked Indigenous people they had abducted from the Massachusetts area, sold them into slavery in the Caribbean, and returned with kidnapped Africans—establishing early slave trading routes just eight years after the colony’s founding.176 In this “Intra-American” trade, Africans kidnapped and taken to the West Indies were trafficked to Boston, where they were sold into slavery.177

Boston was a major site of trafficking and suffering where at least 2,400 kidnapped people arrived directly from Africa.178

The city’s involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade peaked between 1760 and 1775—the same period when Bostonians were staging dramatic protests and escalating their demands for “freedom” and “independence”—when at least 95 voyages departed from or disembarked in Boston, many traveling to or leaving directly from Africa.179

Even after gradual abolition in Massachusetts outlawed the enslavement of Black people, Boston shipbuilders, traders, and businessmen continued to grow wealthy from human trafficking. Boston traders illegally trafficked African women, men, and children for decades after Congress abolished the Transatlantic Slave Trade in 1807. As late as 1858, traffickers aboard the Crimea departed from Boston to Africa, where they kidnapped 600 people from the mouth of the Congo River and sold them in Guanimar, Cuba.180

Imprisoned men at Maula Prison in Malawi who were forced to sleep “like the enslaved on a slave ship.”

Joao Silva/The New York Times/Redux

Traffickers routinely murdered, kidnapped, and tortured Black people on the coast of Africa and during the harrowing Middle Passage to Boston.

In 1645, the Boston-based captain and crew aboard the Rainbow reportedly “joined with London slave raiders in an attack upon an African village, killing about one hundred persons and wounding others.”181 When details of the raid emerged in a Massachusetts court, the court ordered that the two African men brought to Boston aboard the Rainbow be returned to Africa—and ordered that the captain receive compensation for his lost “cargo.”182

Boston traders instructed their captains to inspect the Black people they kidnapped to “take care that they are young & healthy, without any defects in their Limbs, Teeth & Eyes, & as few females as possible.”183 But conditions during the trafficking journey to Boston were so horrific that kidnapped women, men, and children often arrived barely alive.

The business of trafficking was gruesome and brutal. Kidnapped Africans were forced below deck and the men were kept in irons for the entire voyage.184 Phillis Wheatley, a renowned poet, enslaved woman, and native of Gambia who was trafficked to Boston in 1761 as a seven-year-old, arrived in Boston gravely ill and nearly naked, with “no other covering than a quantity of dirty carpet about her.”185

Wealth created by involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade and its related industries—rum, timber, shipbuilding, fisheries, and agriculture—formed the bedrock of Boston’s economy.

In addition to the profits from the trafficking of humans, merchants and businessmen made fortunes from trading raw goods produced by enslaved people.186

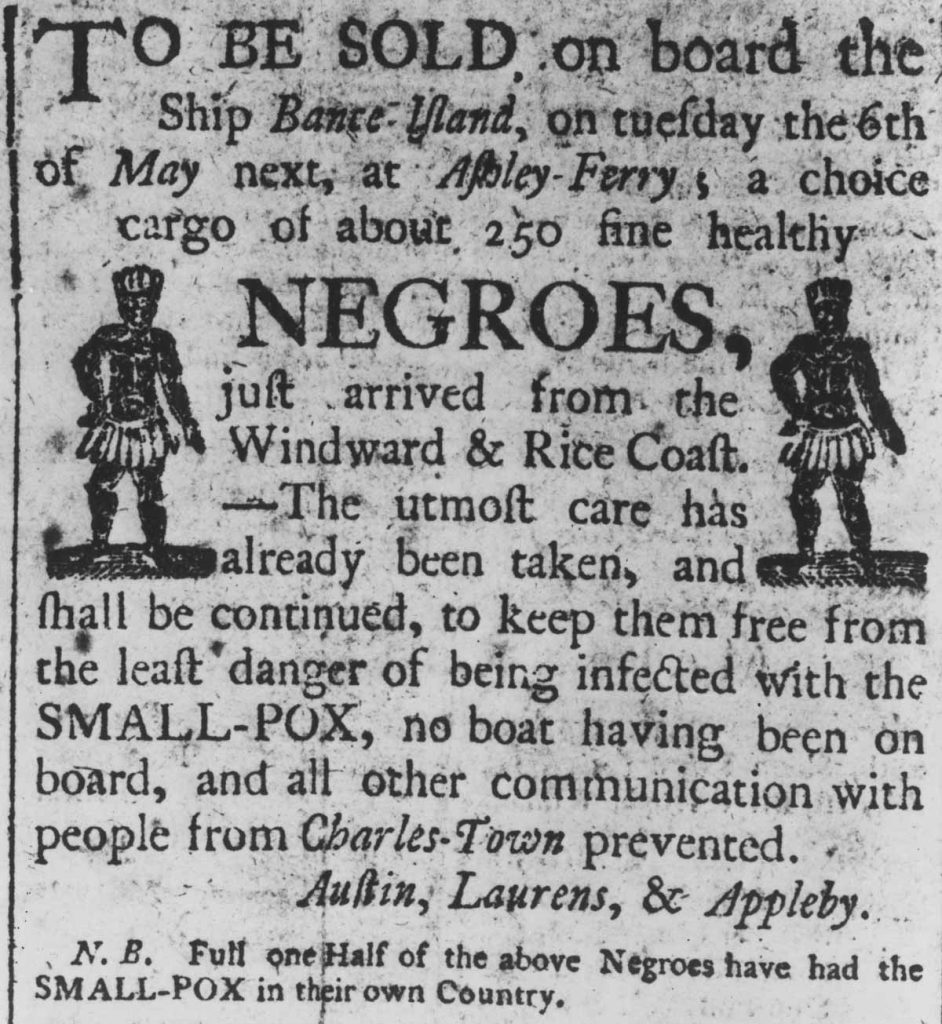

An advertisement for the sale of roughly 250 enslaved people trafficked into Boston on the Bante Island ship, ca. 1700.

MPI/Getty Images

Even after slavery was abolished in Massachusetts, Boston traders flourished by exporting fish, timber, and other supplies that plantations in the Caribbean needed to operate and expand.187

The Boston area became a major producer of rum, which required a steady supply of molasses harvested and refined by enslaved people in the West Indies under conditions infamous for their brutality.188

“The Commerce of the West India Islands, is a Part of the American System of Commerce,” John Adams wrote in 1783, 14 years before he was elected president. “They can neither do without Us nor We without them.”189

Between 1768 and 1772, Massachusetts imported 8.2 million gallons of molasses from the West Indies, and its 63 distilleries produced millions of gallons of rum, mostly for export and to trade for enslaved people.190

Controlling Enslaved People

As the enslaved Black population grew, white Bostonians passed increasingly restrictive regulations to control and socially subordinate enslaved Black people and ensure maximum segregation between Black and white communities.

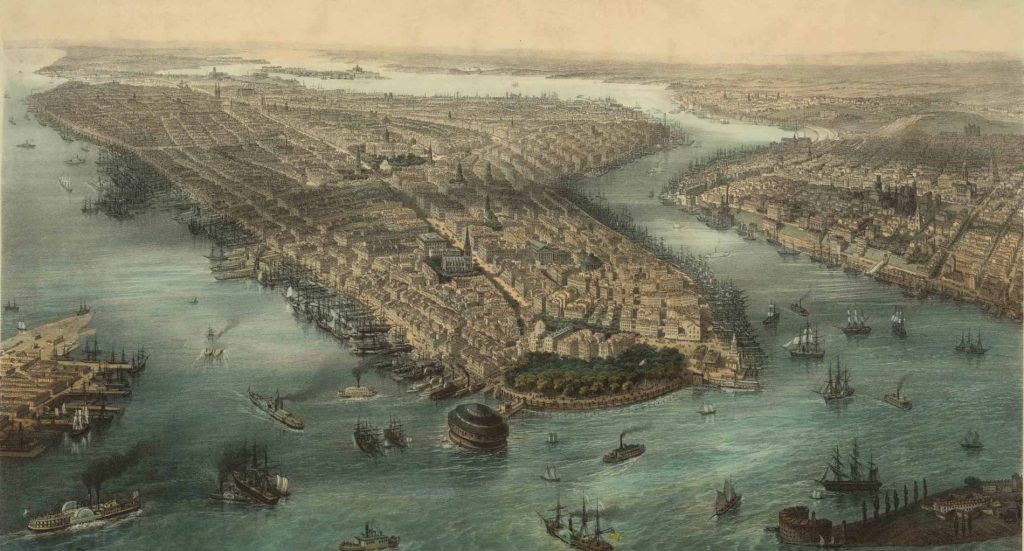

Illustration of the Boston seaport, ca. 1760.

Library of Congress

By 1754, enslaved Black people comprised 10% of Boston’s population.191 Nearly a quarter of all estates probated between 1700 and 1775 listed enslaved people as property.192

One author observed that slavery in Boston was so pervasive in the 18th century that “there is no house in Boston, however small may be its means, that has not one or two [enslaved Black people].”193

To maintain a strict racial hierarchy, Massachusetts prohibited interracial sex and marriage in 1706.194 The law provided that any enslaved Black person who engaged in sexual relations with a white person must be sold and forced to leave the state. That meant Black people who were raped by their enslavers could be forcibly sold away from their families under state law.195

Profiting from Trafficking

In the 19th century, Bostonians invested their profits from the Transatlantic Slave Trade in new manufacturing industries like textiles, which Senator Charles Sumner described as an “unhallowed alliance between the lords of the lash and the lords of the loom.”196

Indeed, not only were large textile manufacturers started with capital reaped from the slave trade, but they also supported enslavement in the South by offering plantation owners a growing market for their products. Francis Cabot Lowell, who used profits from the slave trade to start Boston Manufacturing Company, drove an ever-increasing demand for cotton produced by enslaved Black people when he introduced innovations like the power loom and expanded his textile empire throughout Massachusetts.197

Boston’s most prominent higher education institutions also were enriched by gains from slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

The first president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) enslaved eight Black people in his lifetime.198 Tufts University is on the site of a plantation where at least 27 enslaved Black men and women labored.199

The Royall House on the Royall Plantation in Medford, Massachusetts, where dozens of men and women were enslaved.

Cody O'Loughlin/The New York Times

Harvard University routinely employed professors and administrators who were enslavers and traffickers and relied on enslaved people to cook and clean for students.200

Harvard’s first professorship of law was funded by a bequest from Isaac Royall Jr., the son of one of the largest enslavers in Massachusetts. After his father left him the fortune he had made operating sugar plantations with the enslaved workers he traded between Boston and Antigua, Royall also gifted several properties to Harvard.201

After Abolition

Slavery was abolished earlier in Boston than in much of the U.S., but white Bostonians subjected free Black people to virulent racism, racially discriminatory laws, and strictly enforced racial segregation.202

Even those who advocated for nationwide abolition intended to maintain the racial hierarchy. Renowned Boston abolitionist Theodore Parker celebrated white superiority, saying in a 1857 speech that “the Anglo-Saxon people…is the best specimen of mankind which has ever attained great power in the world.”203

Other prominent Boston thinkers developed “scientific” theories of Black inferiority.

In the 1850s, Harvard professor Louis Agassiz theorized “that the story of Adam applied to only white people and that God had created other races to fit different climates, regions, and ecosystems in the world.” This theory of “polygenesis” helped entrench white supremacy among academics and scientists.204

Harvard professor Nathaniel Shaler argued against interracial marriage in the 1890s and later stated that Black children had an “animal nature” that would emerge as they grew up.205

To protect the racial hierarchy, Black Bostonians were denied full citizenship rights. They were not allowed to vote or sit on juries, and were frequently humiliated by racist displays in popular culture.206 They were also forced to live with the very real threat that they could be abducted, transported to a state or country where slavery remained legal, and enslaved.207

After abolition, Black people in Boston faced more than a century of court-enforced discrimination in housing and education.

Restrictive racial covenants and intimidation prevented Black families from renting and buying homes. In 1935, 100 Black families were evicted from present-day Cambridge to make way for an all-white neighborhood, and after World War II, Boston built 25 public housing projects that were segregated by race.208

Racial segregation permeated the city’s schools as well. Between 1933 and 1943, only six Black students graduated from Boston College, and in the 1950s, more than 80% of Boston’s Black elementary school students attended majority-Black schools.209

Calls to implement busing to desegregate Boston’s school system in the 1970s were met with massive, violent protests by white parents, who pulled 30,000 children out of the public school system.210 Today, only about 14% of public school students are white in a city that is about 45% white.211

Racial hierarchy and economic inequality between Black and white Bostonians have deep roots in the Transatlantic Slave Trade that persist in the city to this day.

Chapter 4

New York, New York

In this Chapter

- Trading on Wall Street

- Laws Targeting Black People

- An Economy Founded on Slavery

- Post-War Racial Discrimination

Enslavement is a defining feature of New York City’s origin story. New York City was a critical port in the Transatlantic Slave Trade, resulting in the trafficking and sale of thousands of kidnapped Africans on Wall Street.

Enslaved people cleared and cut the road that would become Broadway, built the wall that Wall Street was named for, paved the roads that expanded the city uptown, and grew crops in Brooklyn to feed their enslavers.212

Almost half of New Yorkers in 1730 personally enslaved Black people—a higher percentage than any colonial city except Charleston, South Carolina.213

“Free” Black people in New York City faced violence, segregation, and constant threats of being kidnapped, labeled a “fugitive slave,” and sold into slavery in the South.214 In the decades following the Civil War, Black people were viewed as suspects, criminalized, subjected to Jim Crow laws and customs, and denied equal housing and educational opportunities.

Watch: New York City was a major port in the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Trading on Wall Street

In 1626, the Dutch West India Company trafficked 11 enslaved Africans to New Amsterdam, a Dutch settlement established that year that would become New York City.215 By the early 1630s, approximately 100 of the city’s 300 residents were enslaved.

The company forced enslaved men and women to build New Amsterdam’s fort, develop the colony’s infrastructure, clear and cut the road that became Broadway, and “stand guard” against the Native people who lived there before European settlers arrived and colonized their land.216

As early as 1644, enslavement was reinforced as a hereditary status for Black people.

When New Amsterdam’s first 11 enslaved people petitioned for “half-freedom” in 1644—which gave them conditional freedom if they paid an annual fee to the company and agreed to assist the company when needed—the company agreed, but only “[w]ith the express condition that their children, at present born or yet to be born, shall remain bound and obligated to serve the honorable West India Company enslaved.”217

In 1655, the Witte Port, a large ship into which “slave traders had tightly packed three hundred African men and women and left them to travel across the Atlantic amid their own waste” docked in New Amsterdam.218

By 1660, New Amsterdam was the “most important slave port in North America.”219

Researchers have documented at least 70 different Transatlantic ships trafficking enslaved people between 1651 and 1775 whose “principal place of slave landing” was “New York, New York.”220 From 1651 to 1775, at least 7,209 enslaved Africans disembarked in New York City.221

Most trafficking ships docked at the Port of New York in Lower Manhattan. In 1711, New York City opened an official market for the trafficking of enslaved people on Wall Street, which became the central location for the trading of enslaved people.222

By 1730, 42% of New York City’s white residents directly enslaved Black people.223 For most of the 18th century, enslaved people comprised approximately 20% of the city’s population.224

Laws Targeting Black People

White New Yorkers justified exploiting the labor of enslaved people to build their city, with false narratives of racial difference rooted in white supremacy and Black inferiority.225

The ideology of inferiority included the myth that Black people were inherently dangerous, a false idea that was employed to justify swift, brutal, and violent responses to any threat to the social order.

In 1712, when a group of enslaved people engaged in an uprising and asserted their right to freedom, the government responded by executing 21 enslaved people—of whom the majority were hanged, some were burned alive, while one person was tortured to death on a breaking wheel—and passing new restrictions on enslaved people’s activities.226

The New York State Assembly made it a crime for any enslaved person to possess or use “any gun Pistoll [sic] sword Club or any other Kind of Weapon.”227 It was illegal for three or more enslaved people to congregate unless it was “in some servile imployment [sic] for their Master or Mistress.”228 Enslaved people were further prohibited from being on the streets after dark, unless with their enslavers.229

The New York Assembly discouraged emancipation by requiring an enslaver to pay a £200 tax or fee (over $50,000 today) for each emancipated person.230

These new laws both reflected and encouraged the race-based fears of white New Yorkers. In March and April 1741, a series of fires across New York City were blamed on the city’s enslaved population and treated as coordinated acts of arson.231 Hysteria ensued, and city officials initiated a “mass arrest of the [enslaved] population of the city,” forcing so many people into city jails that “the magistrates feared a plague.”232

A series of sensational trials began only weeks after the fires and dozens of enslaved people were convicted largely on the testimony of a paid 16-year-old white informant. City officials hanged 18 enslaved people, burned 13 people to death, and banished more than 70 to bondage in the West Indies.233

The numbers of kidnapped Africans who disembarked in New York increased from 916 people between 1700 and 1725 to 1,211 between 1726 and 1750.234 From 1751 to 1775, at least 3,583 kidnapped African people were trafficked through New York City, nearly three times the number during the previous 25 years.235 By 1771, 33% of the residents of modern-day Brooklyn were enslaved African people.236

An Economy Founded on Slavery

New York State did not officially abolish slavery until 1827.237 Even after abolition, New York City remained invested in enslavement and continued to profit from human bondage. By some estimates, the city received 40% of U.S. cotton revenue through its financial firms, shipping businesses, and insurance companies.238

Insurance companies based in New York, including New York Life Insurance Company and Aetna, Inc., which are the country’s largest life and health insurance companies today, sold policies that reimbursed enslavers for financial losses when the people they enslaved died.239

An illustration of New York City, ca. 1850.

Banks based in New York, such as Citizens Bank and Canal Bank—which later became part of JP Morgan Chase—accepted enslaved people as collateral on loans and “collected” 1,250 Black people when plantation owners defaulted.240

The National City Bank of New York (the predecessor bank of Citibank, which today has offices at 111 Wall Street) was founded by a white man named Moses Taylor, a banker and sugar trader who helped finance the Transatlantic Slave Trade after it was outlawed in 1808.241 Mr. Taylor was one of the wealthiest men in the 19th century, with an estate reportedly worth $70 million (about $1.6 billion today).242

New York City courts regularly returned formerly enslaved people to white enslavers who made claims under the Fugitive Slave Act.

Many of these lawsuits were presided over by judge Richard Riker, a former enslaver who city constable Tobias Boudinot once boasted could “arrest and send any black to the south.”243 Judge Riker often classified Black people as “fugitive slaves” without due process of law. He is the namesake of Rikers Island, where thousands of Black New Yorkers are currently confined in one of the country’s most inhumane and overcrowded jail systems.244

A sign for Rikers Island correctional facility in New York.

Library of Congress

In the 1840s and 1850s, New York’s political leaders and media argued that nationwide emancipation would harm employment prospects for white working-class men. Horatio Seymour, a devout white supremacist who served as governor of New York from 1853 to 1854 and 1863 to 1864, warned against abolishing slavery,245 and New York City voted against Abraham Lincoln in both the 1860 and 1864 presidential elections.246

“The scheme for an immediate emancipation and general arming of the slaves throughout the South is a proposal for the butchery of women and children, for scenes of lust and rapine, of arson and murder unparalleled in the history of the world.”

New York Gov. Horatio Seymour

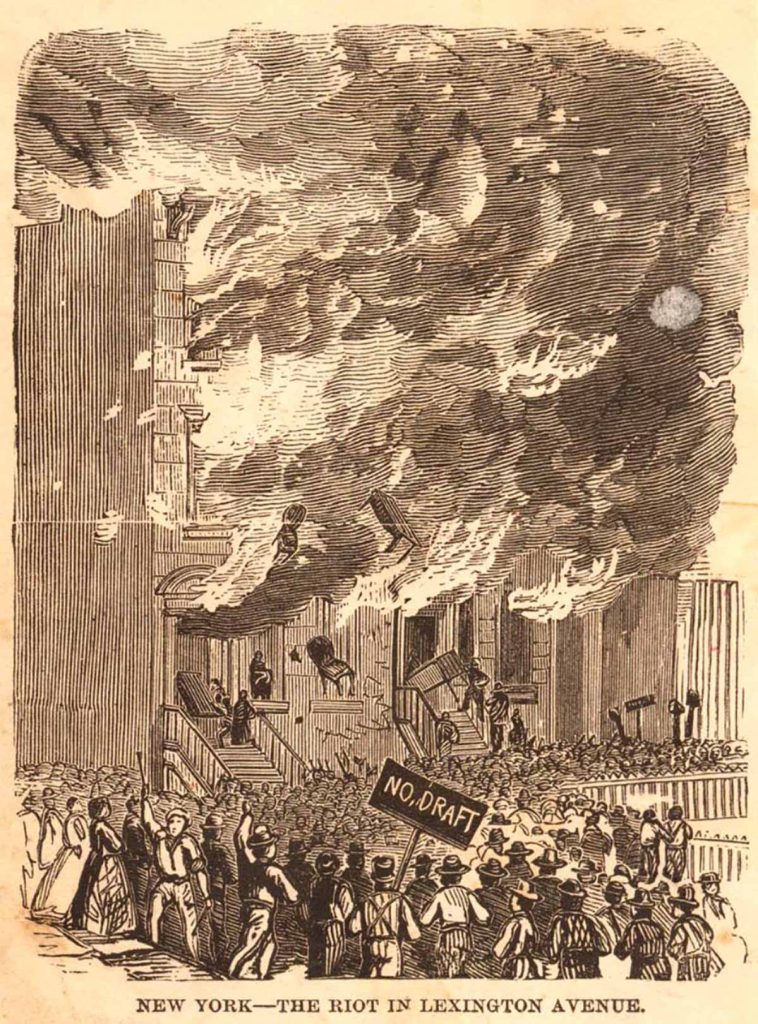

In the summer of 1863, after Congress authorized the drafting of men to fight for the Union in the Civil War, white residents of Manhattan and Brooklyn viciously attacked hundreds of Black people in a racially-motivated massacre that became known as the Draft Riots.247

White people killed approximately 100 Black people in Manhattan and Brooklyn between July 13 and 16. One historian detailed the brutality of the white rioters:

On the waterfront, they hanged William Jones and then burned his body. White dock workers also beat and nearly drowned Charles Jackson, and they beat Jeremiah Robinson to death and threw his body in the river.

Rioters also made a sport of mutilating black men’s bodies, sometimes sexually. A group of white men and boys mortally attacked black sailor William Williams—jumping on his chest, plunging a knife into him, smashing his body with stones—while a crowd of men, women, and children watched. None intervened, and when the mob was done with Williams, they cheered, pledging ‘vengeance on every nigger in New York.’

A white laborer, George Glass, rousted black coachman Abraham Franklin from his apartment and dragged him through the streets. A crowd gathered and hanged Franklin from a lamppost as they cheered for Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president.248

An illustration from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper of the 1863 “Draft Riots” in New York.

New York Public Library

The violence was committed openly by known individuals, but no white people were ever held accountable. As a result of this racial terrorism, “for months after the riots, the public life of the city became a more noticeably white domain.”249

Racial terrorism permanently shaped the demographic geography of New York City.

In 1860, the Black population of New York City was 12,472. By 1865, the Black population had decreased to 9,943.250

Post-War Racial Discrimination

In the decades following the Civil War, Black people were overpoliced, criminalized, subjected to Jim Crow segregation, and denied equal housing and educational opportunities. The legacy of this history has never been confronted.

Even today, racial disparities can be found in New York City that reflect a long history of racial bias, especially in the criminal legal system. The Rockefeller Drug Laws signed into law by Gov. Nelson Rockefeller in 1973,251 NYPD’s “stop and frisk” policies in the 1990s, and residential racial segregation have led to racial disparities. Nearly 94% of people in state prison in 2002 were Black or Latino, with the overwhelming majority coming from New York City.252

In 2010, the New York metropolitan area had the third highest level of residential segregation among the 50 largest metropolitan areas in the U.S.253 Similarly, a 2014 report found that New York City’s educational system is among the most racially segregated in the country.254

Chapter 5

The Mid-Atlantic

In this Chapter

- A Hub for Human Trafficking

- Work of Enslaved People

- Separating Families

- Controlling Black People

- A Legacy of Racial Bias

Trafficking in Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Washington began as early as 1626, when the Dutch West India Company trafficked kidnapped Africans to “New Netherland.”255 In 1630, 50 African people enslaved on a plantation across the Hudson River became “the first Black residents of New Jersey.”256

In 1664, a “Concession and Agreement of the Lords Proprietors of the Province of New Cesarea, or New Jersey” granted land to white settlers for every enslaved person they brought into the province. The number of acres depended on the enslaved person’s age and strength.257 Called the colony’s first constitution, the concession legalized slavery as an institution and made it foundational to the region’s economy.258

As in New Jersey, white settlers in Maryland almost immediately codified the enslavement of Black people. British colonists arriving in Maryland in the 1630s brought enslaved Black people with them from Europe.259

Following initial colonization, trafficking also commenced in Maryland—colony proprietor Lord Baltimore directed his agent to purchase 10 enslaved Africans to work his land. In 1642, his younger brother, Leonard Calvert—who would later be appointed the first governor of Maryland—sought “fourteen negro men-slaves, and three women-slaves, of betweene 16 and 26 years old.”260

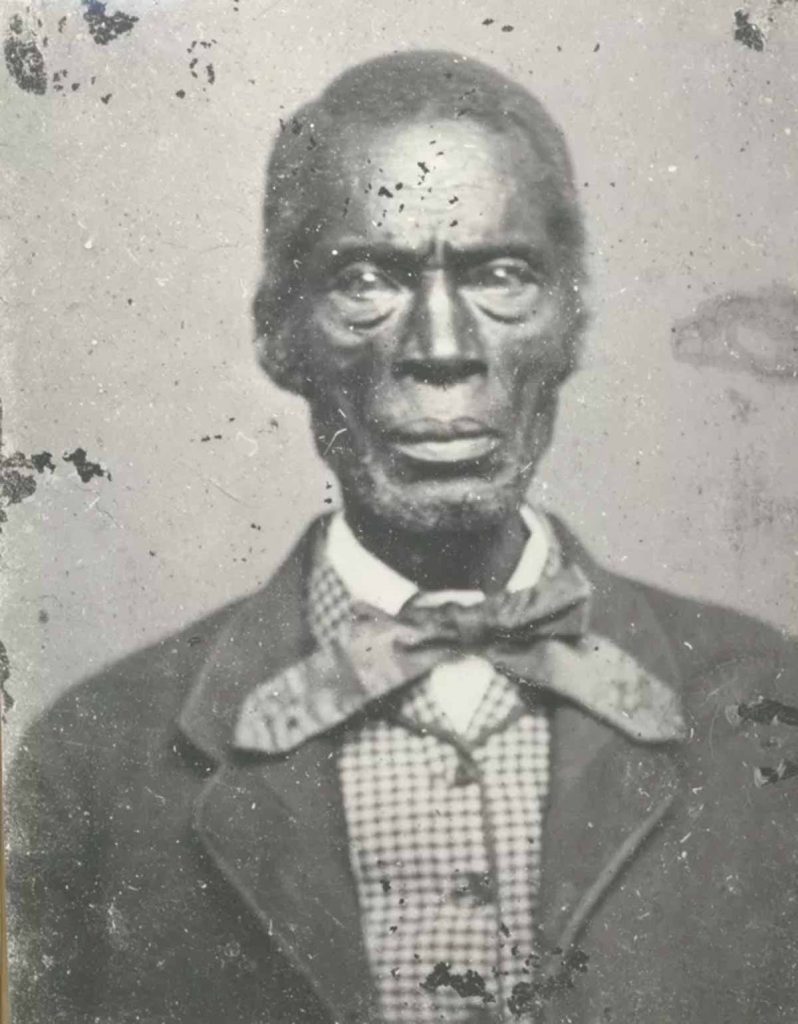

A photograph of Frank Campbell, ca. 1900. Mr. Campbell was one of 272 enslaved people sold by the Maryland Jesuits in 1838.

Robert Ruffin Barrow, Jr. Papers, Archives and Special Collections, Nicholls State University, Thibodaux, LA

The colony passed laws defining enslaved people as subordinate as early as 1639, when a Maryland law held that all Christians, “[s]laves excepted,” held the rights of Englishmen.261

In 1664, an act of Maryland’s colonial assembly transformed slavery into a permanent, hereditary, and race-based legal status.262

In Pennsylvania, trafficking of enslaved Africans began in 1639. Pennsylvania was founded by Quakers, who later opposed slavery, but many Quaker families enslaved people in early colonial settlements.263

The first enslaved Black person trafficked to Delaware was a man named Anthony, who was captured in 1638 and arrived in Delaware in 1639.264

A Hub for Human Trafficking

Between 1662 and 1800, at least 136 Transatlantic slave voyages landed in the Mid-Atlantic and sold thousands of kidnapped Africans into captivity in local markets and ports.265 These ships trafficked 27,829 enslaved people, including more than 5,000 who died from disease, injury, starvation, or suicide during the gruesome Middle Passage.266

Maryland’s desire to exploit enslaved labor far outpaced the other Mid-Atlantic colonies.

To encourage the use of ports in Maryland and Washington, Maryland imposed much lower import taxes than neighboring Virginia.267 At least 25,844 people were kidnapped from Africa and trafficked to Maryland alone.268

An illustration published in Harper’s Magazine in 1901 shows trafficked Africans arriving in Jamestown, Virginia.

Howard Pyle/Private Collection, via Bridgeman Images

The Mid-Atlantic region was also responsible for trafficking enslaved Black people to other parts of the world. Between 1695 and 1865, 25 Transatlantic voyages departed from Mid-Atlantic ports carrying 4,634 enslaved Black people, 1,090 of whom died during the journey.269 Seven of these voyages occurred after the Transatlantic Slave Trade was abolished in 1808.270

Mid-Atlantic traffickers also actively trafficked enslaved people to and from the West Indies and between U.S. colonies.271 In total, 13,178 Black people were purchased in the Mid-Atlantic and trafficked to other countries on 479 different voyages between 1695 and 1831.272

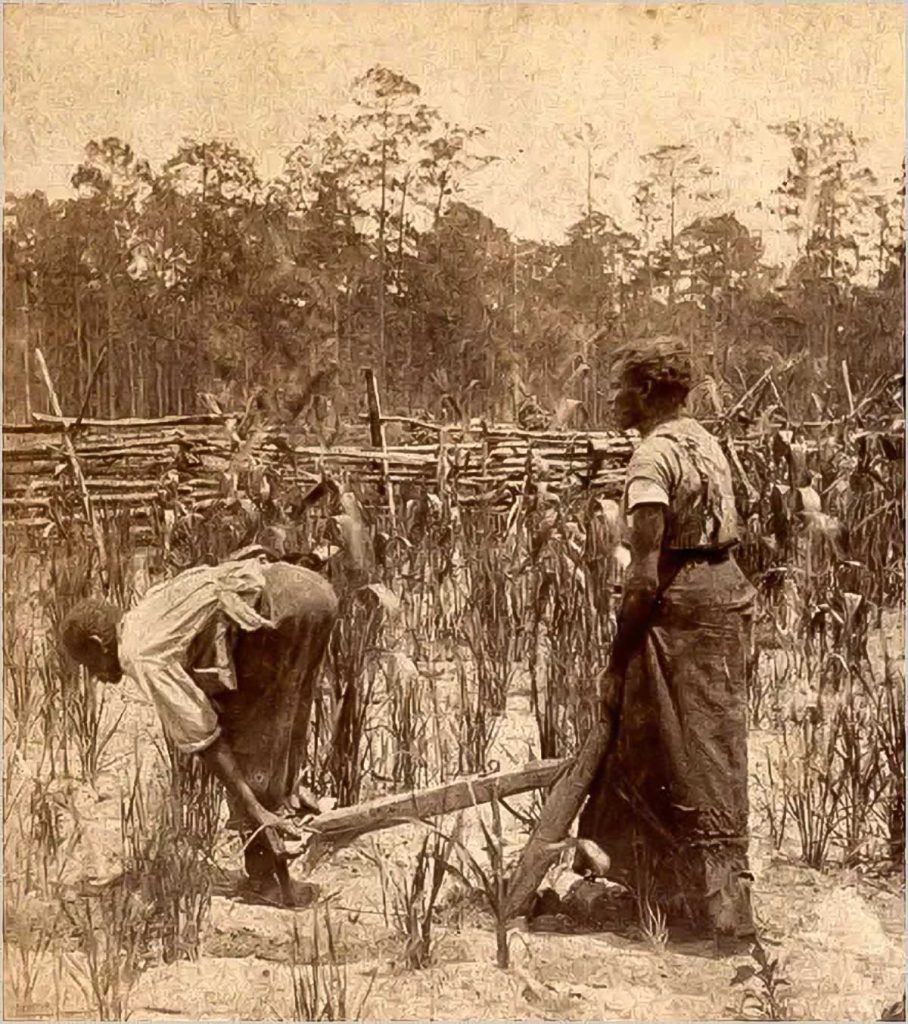

Work of Enslaved People

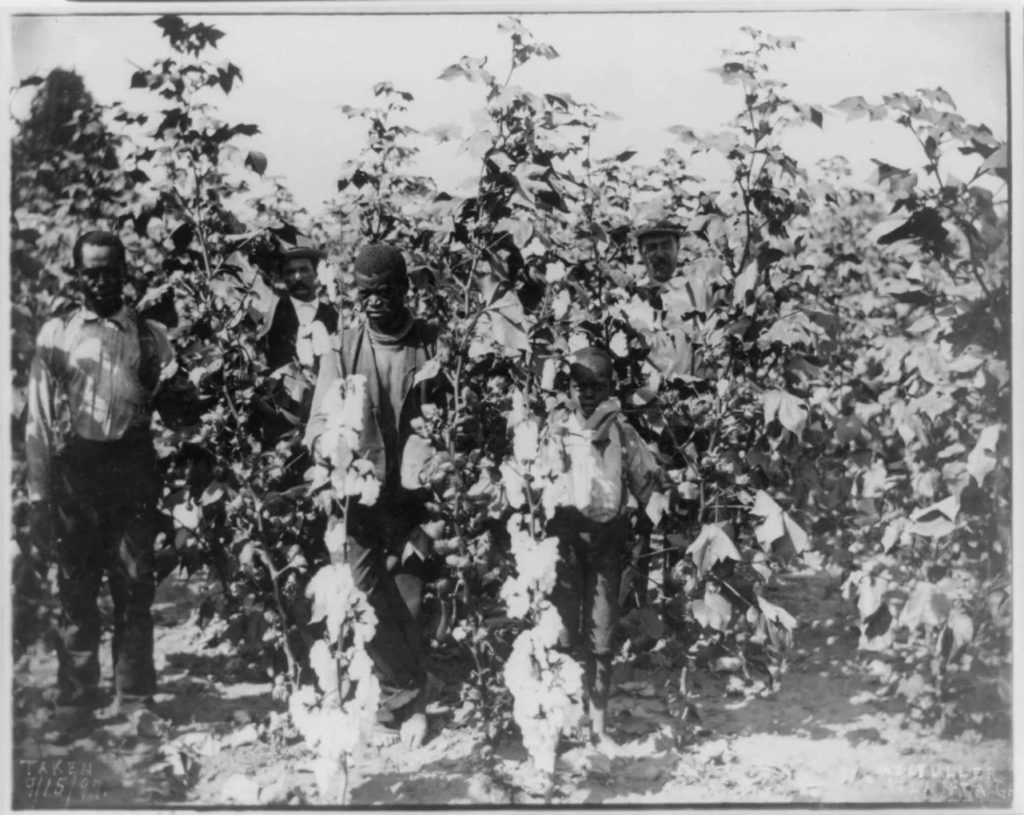

The forced labor performed by enslaved Black people in the Mid-Atlantic varied widely and included harvesting grain, producing meat and dairy products on small farms, building homes, blacksmithing, butchering, tanning and leatherwork, carpentry, carriage driving, cooking, cleaning, and mining.273

Brutality was the constant, as even “the lives of enslaved artisans were marred with the same physical, emotional, and psychological violence as their counterparts who performed domestic and agricultural labor.”274

Iron mines in Monmouth County, New Jersey, relied heavily on the labor of enslaved people. One of the earliest records of enslaved Africans in New Jersey comes from Col. Lewis Morris’s estate.275 Morris assigned skilled labor to free white workers and hard physical labor to enslaved Africans, requiring the groups to live in separate dormitories on his property.276 These measures “established unequal, race-based ranks among the laborers,” setting the stage for future racial discrimination in industrial settings in Monmouth County.277

A tobacco field on the Wessyngton Plantation in Tennessee.

Library of Congress

Tobacco-farming enslavers on Maryland’s fertile Western Shore became the colony’s first large-scale investors in Transatlantic trafficking.278

By the 1690s, enslaved Black people in Maryland outnumbered European servants two-to-one. By 1700, Maryland tied with Virginia as the single largest trafficking destination in North America.279 Enslavers in the Western Shore counties had transitioned completely to enslaved African labor by 1710.280 In 1864, just before the end of the Civil War, 140,000 enslaved and free Black people worked in tobacco and cereal fields in Maryland.281

More than 100 ships used in the Transatlantic Slave Trade were constructed in the Mid-Atlantic region.282

In Pennsylvania, enslaved Black people were forced to build some of these ships and make sails.283 A 1768 posting in the Pennsylvania Gazette advertised the sale of “[f]our healthy young Negroe Men…brought up to the sail-making trade; they have been from nine to twelve years at said trade.”284

These ships continued to traffic kidnapped African men, women, and children long after the federal government banned the international slave trade in 1808, with trafficking voyages departing the Mid-Atlantic as late as 1856.285

Enslaved Black people in the Mid-Atlantic often lived in the homes of their enslaver, where they were subject to constant surveillance.286 Outside the home, enslaved people lived under strict curfews enforced by violent punishments. Passed in 1725, Pennsylvania’s curfew law stated that “any negro…found out of or absent from his master or mistress’s house after nine o’clock at night without license from his said master or mistress, [he] shall be whipped on his or her bare back.”287 New Jersey’s 1751 law also imposed a 9 pm curfew on enslaved Black people and made violations punishable by whipping.288

Separating Families

After 1808, Washington, D.C., became a popular hub for the Domestic Slave Trade. Enslaved people were brought to the nation’s capital “as if it were an emporium of slavery” and then transported to the Deep South to be sold.289

Many downtown hotels and taverns were used in the slave trade. Several dedicated blocks of rooms for the temporary housing of enslaved people and for enslavers and traffickers who traveled to Washington to engage in the Domestic Slave Trade.290

One known slave pen was right across the street from the White House291 and Black people were also held in pens near and on the National Mall.292 The D.C. jail offered to warehouse people for traffickers for 34 cents per day.293

In 1815, an enslaved Black woman was being held in a tavern on F Street in downtown Washington prior to being sent to the South with a coffle. Human traffickers had separated her and her two children from her husband. Desperate to escape, she jumped from a third story window and broke both arms and her back. She survived but the traffickers left her behind and took her children to be sold in the South.294

Family separation was commonplace in the Mid-Atlantic, where enslavers had no concern for the precious family ties that enslaved people managed to create under horrific, dehumanizing conditions.

Children were often separated from their families and sold alone.295 Even when they were not sending family members to distant plantations, enslavers rarely permitted Black families to live together.296

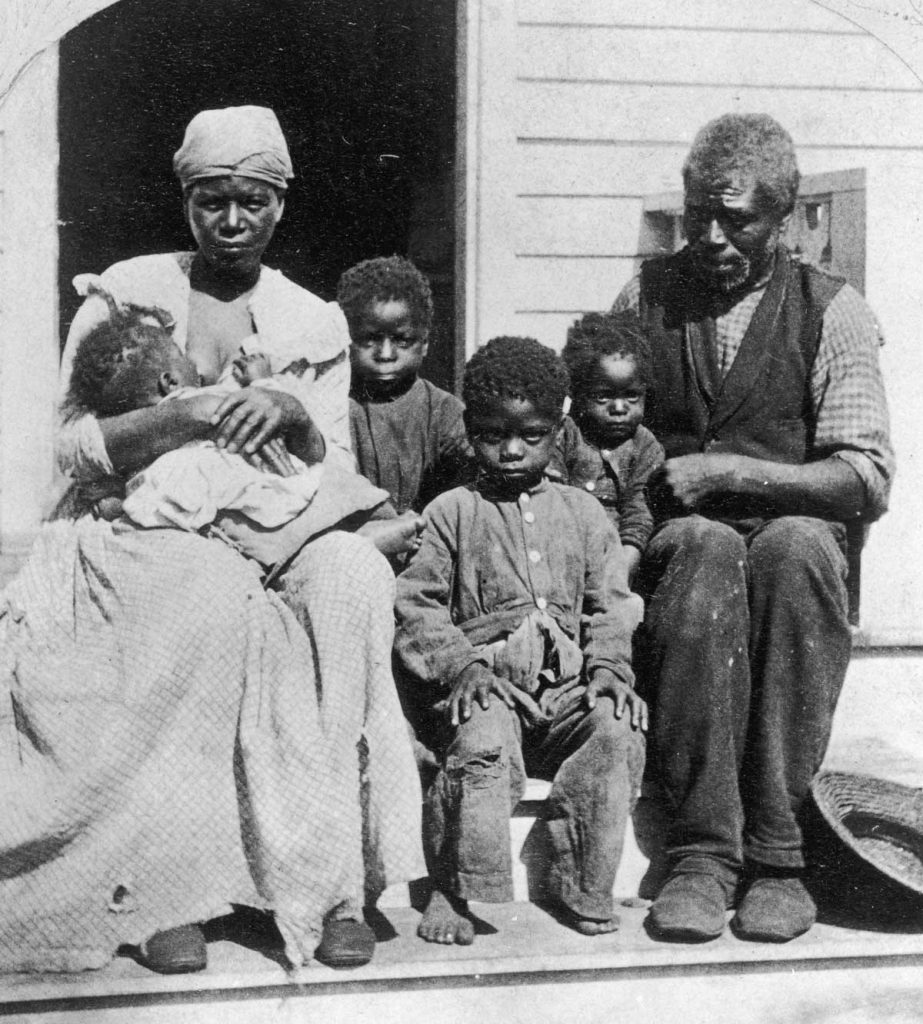

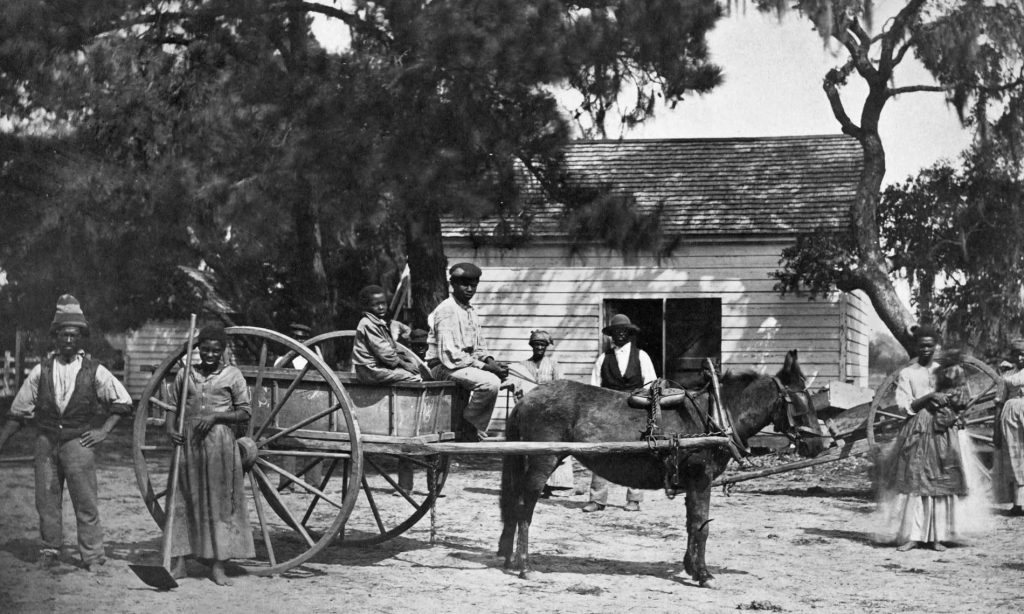

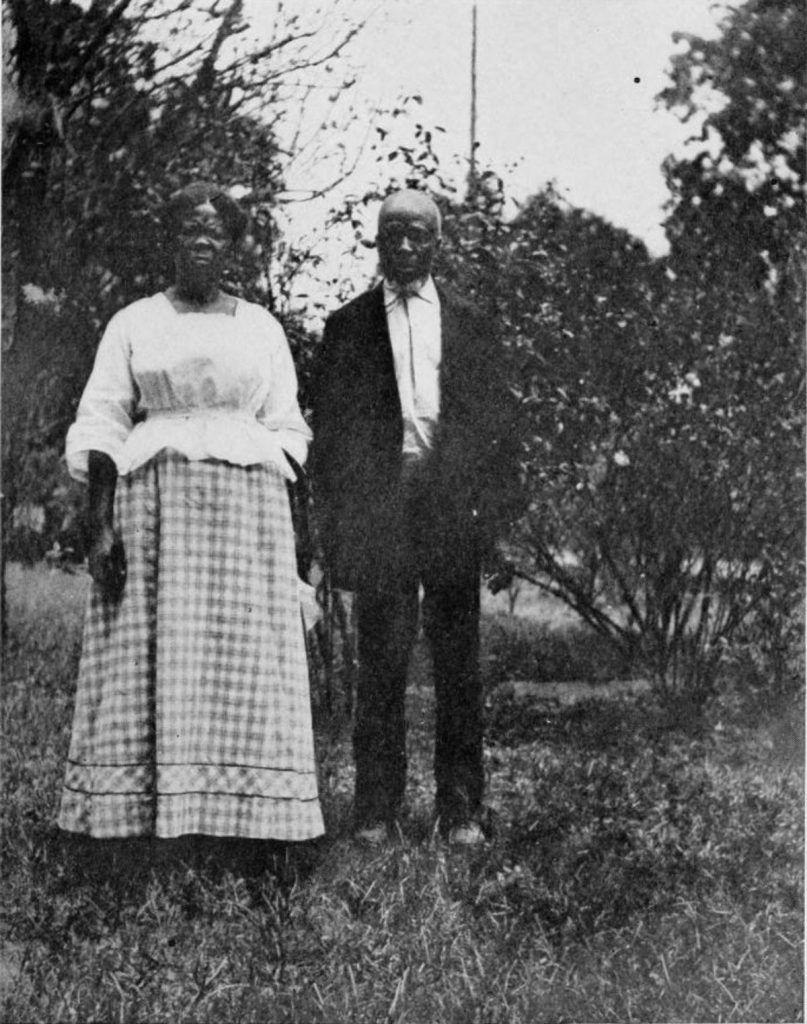

An enslaved family, ca. 1850.

Fotosearch/Getty Images

Laws intended to prevent enslaved people from straying from their enslavers also separated families.

A 1704 New Jersey law provided that if an enslaved person was more than 10 miles from their home, any person could capture them, whip them 20 times, and obtain a reward for returning them to their enslaver.297

After the Civil War, enslaved people risked their lives and traveled great distances, even with small children in tow, to reunite with loved ones.298

Controlling Black People

To uphold slavery as a permanent condition tied to race, states in the region enacted punitive laws targeting and regulating free Black people. In 1698, Maryland Gov. Francis Nicholson voiced many white enslavers’ fears when he said that allowing free Black people freedom of movement, combined with growing numbers of enslaved Black people, might lead to “great disturbances if not a rebellion.”299

In 1715, building on these narratives, Maryland prohibited free Black people from socializing with or “entertain[ing]” enslaved people.300 Another Maryland law was passed in 1723 to prevent “the evil Consequences that do and may attend the Suffering of Negro and other Slaves to meet in great Numbers on Sabbath and other Holy-Days.”301

The colonies also passed laws prohibiting gatherings of more than four or five enslaved Black people. In 1700, Pennsylvania, of which Delaware was then a part, prohibited Black people from gathering “in great companies or number.”302 If more than four Black people gathered, they were to be severely and publicly whipped.303

A 1704 law in New Jersey prohibited Black people from entering the colony without written permission from their enslaver.304 The law authorized any white person to capture a Black person suspected of entering without permission and “he, she or they so taken up shall be whipt at the publick Whipping-post.”305 The law effectively barred free Black people from entering New Jersey because they had no enslaver to provide the required license.306

Colonies in the Mid-Atlantic restricted free Black people’s ability to establish economic independence.

A 1713 New Jersey law prohibited formerly enslaved Black or Native people from purchasing or owning land, stating “no Negro, Indian or Mulatto Slave, that shall hereafter be made free, shall enjoy, hold or possess any House or Houses, Lands, Tenements or Hereditaments within this Province.”307

As late as 1849, Delaware passed legislation providing for the forced enslavement of free Black people based on the assertion of a white person that they could not support themselves.308 Pennsylvania passed a mandatory forced servitude law in 1725 that provided “if any free Negroe fit and able to work, shall neglect so to do, and loiter and mispend his or her Time or, wander from Place to Place, any two Magistrates next adjoining are hereby impowered and required to bind out to Service such Negroe from Year to Year, as to them shall seem meet.”309

Eventually, colonies in the Mid-Atlantic passed legislation that outright prohibited free Black people from living in their communities.

In 1807, Delaware banned free Black people from moving into the state.310 Any who did, and remained for 10 days, would be warned to depart. If they refused, they would be fined. If they could not afford the fine, they would be sold into servitude “not exceeding seven years.”311 Exceptions were made for those who had both a certificate of freedom and a certificate signed by two justices of the peace in the state from which they came that asserted they were of “good moral character, and industrious habits.”312

A woman named Jints, who was enslaved by James Anderson in Delaware, holds a young girl named Hanna Stockley, ca. 1860.

Delaware Public Archives

To disincentivize enslavers from setting enslaved people free, every Mid-Atlantic community required that the freed person or their former enslaver pay a fine in order for that person to live in the colony and remain free.

A 1713 New Jersey law required enslavers to pay a security of £200 (about $13,800 today) per year for the rest of the formerly enslaved person’s life.313 If an enslaver chose to free an enslaved person through their will and the enslaver or enslaver’s executor failed to pay the yearly security, “said Manumission to be void, and of none Effect.”314

These laws often codified racist tropes and reinforced the ideology of Black inferiority.

A Delaware law limited emancipation because “it is found by experience, that free Negroes and Mulattoes are idle and slothful, and often prove burdensome to the neighborhood wherein they live, and are of evil example to slaves.”315

Free Black people in the Mid-Atlantic lived in constant fear of being kidnapped and trafficked to the Deep South. Their fear was well founded.

Days after her husband died, a young, pregnant, and free Black woman was seized from her bed by her landlord and other white men, who placed a noose around her neck and repeatedly struck her in the head with a wooden stick when she resisted.316 She was trafficked from Maryland to Washington, where she was forced to await sale to Georgia. While she and her infant child managed to obtain their freedom before being taken South—potential buyers “refused to purchase, on account of her asserting she was free”—countless individuals were not so fortunate.317

An exhibit at the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, uses technology to share stories of enslaved people and the trauma of being separated from loved ones.

Andrea Morales/The New York Times

Each colony in the Mid-Atlantic passed legislation prohibiting the importation of enslaved Black people from Africa prior to the federal government’s ban on the Transatlantic Slave Trade in 1808.318 But communities in the Mid-Atlantic continued to be originating ports in the Transatlantic Slave Trade and to benefit from the institution of slavery.

New Jersey banned the importation of enslaved Black people in 1786,319 but the law prevented the importation or sale only of enslaved people who had been kidnapped from Africa after 1776.320 As a result, enslaved people who were kidnapped and trafficked from Africa before 1776 could still be sold and trafficked to New Jersey.

While New Jersey’s law would eventually prohibit the removal of enslaved people from the state without their consent, or the consent of their “guardians,”321 enslavers could simply forge an enslaved person’s signature. Surviving bills of sale “reveal that 41 percent of slaves ‘consented’ to removal to the Deep South, showing that coercion of some sort was likely common.”322

One of the most notorious examples of coercion was a human trafficking organization established by Judge Jacob Van Wickle and his brother-in-law, Charles Morgan, a Louisiana state legislator. The judge would falsely attest to the consent of enslaved people, including children, who were transported to Louisiana and other states in the lower South.323

Judge Van Wickle continued to mastermind illegal trafficking even after the passage of New Jersey’s gradual abolition act in 1804. As a result, enslaved children who would have been freed as they aged in New Jersey, were instead trafficked to the South where they faced a lifetime in bondage.324

During the Civil War, Delaware resisted all efforts at abolition within the state, including President Abraham Lincoln’s 1861 proposal to compensate Delaware’s enslavers using federal funds if they would free the Black people they held in bondage. The Delaware legislature replied to President Lincoln’s proposal with a resolution stating that “when the people of Delaware desire to abolish slavery within her borders, they will do so in their own way, having due regard to strict equity.”325

When President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, he explicitly exempted Maryland and Delaware, which allowed enslavement to continue there during the Civil War.326

Even after the Civil War, Delaware staunchly opposed abolition.

It refused to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, or the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, which extended civil rights and voting privileges to Black men.327 Delaware finally ratified the Thirteenth Amendment on February 12, 1901—more than 30 years after it became part of the Constitution.328

A Legacy of Racial Bias

White communities in the Mid-Atlantic found many ways to restrict and regulate Black people’s lives for decades after emancipation. Today, the region continues to grapple with racial segregation in both housing and education.

In Maryland, public schools were closed to Black children for seven years after the Civil War.329

In Washington, separate but unequal schools for Black children continued to operate well beyond 1954 through a track system that created discriminatory outcomes.330

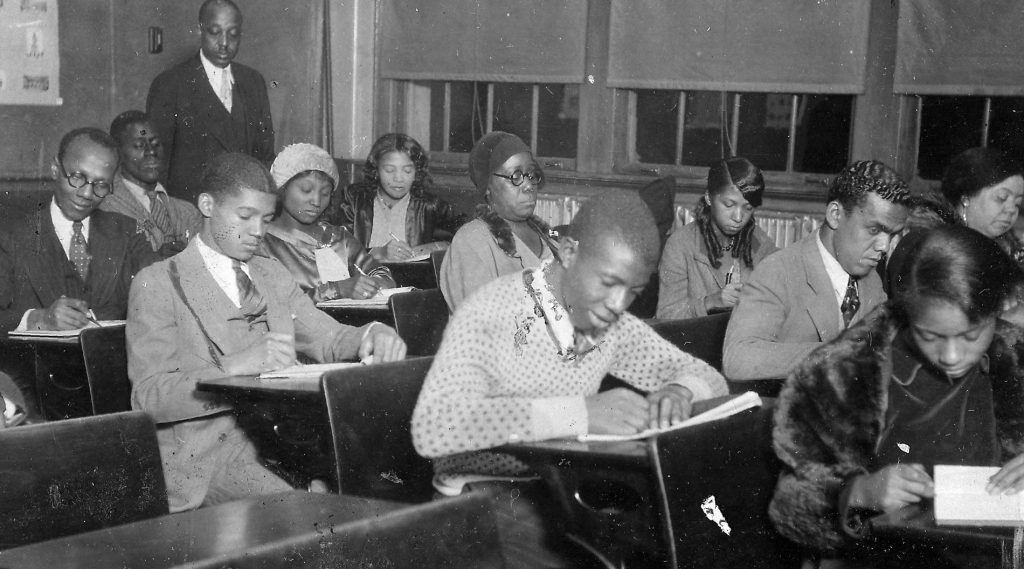

Black students attend an evening class at the segregated Frederick Douglass High School in Baltimore, Maryland, on February 7, 1930.

Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

“New Jersey is one of the most racially and ethnically diverse states in the country—but it is also one of the most segregated.”331

In the 1940s, “racial covenants served to confine the vast majority of DC’s expanding Black population to older housing near the city center, near waterfront employment along the Potomac and Anacostia rivers, and to remote sections of far Northeast and Southeast DC.”332

Housing segregation became entrenched and persists in Washington today.333

Black people in Washington make up 45% of the nearly 690,000 people living there as of the 2020 Census, but they have no real representation in Congress.334

Black people in the Mid-Atlantic continue to be disproportionately incarcerated at rates above the national average. Today, the disparity in the incarceration rate between Black and white people in New Jersey is 12.5 to 1, compared to 4.8 to 1 nationwide.335 In Pennsylvania, the disparity is 7.4 to 1, meaning a Black person is almost eight times more likely to be incarcerated than a white person.336

Chapter 6

Virginia

In this Chapter

- Tobacco Drives Trafficking

- Legislating Hereditary Enslavement

- Laws Controlling Lives

- The Domestic Slave Trade

The first kidnapped Africans trafficked to British North America in the Transatlantic Slave Trade arrived at Jamestown, Virginia, on a Portuguese trafficking vessel in 1619.337

In 1662, Virginia specified that every child born to an enslaved Black woman was enslaved for life—making it the first British North American colony to formally mandate race-based, hereditary enslavement.338