‘No words for the anxiety’: migrants desperate for jobs trapped in US asylum maze

"Many people are already eligible for work permits through ‘parole’ program – but a bureaucratic fog obscures the process

Mayor Eric Adams of New York City is fed up with providing a welcome for an influx of migrants seeking asylum. At a town hall meeting last week, he declared that spending on shelters and care, more than $5bn this year alone, “will destroy New York City”.

After more than 107,000 migrants arrived over the last year, almost 60,000 are still living in some 200 city shelters. The system was already strained; now it’s overwhelmed. Adams, a Democrat, has been haranguing Joe Biden on one issue in particular: he wants faster authorization for asylum seekers to work legally, so they can become self-supporting and move off city services.

As a presidential election year approaches, immigration is once again a political cudgel, and Democrats are fearful they will suffer at the polls. In late August, Kathy Hochul, the New York governor, joined the rising clamor from Democrats, meeting with officials at the White House. Maura Healey, the governor of Massachusetts, declared a state of emergency over migrants arriving in the state.

After many months when federal officials were reluctant to engage the prickly problem, the White House relented, with a solution that had been hiding in place.

Hundreds of thousands of migrants, officials said, were already eligible to apply for work permits. They had entered the country on a temporary permission known as parole, which allows them to avoid a 180-day waiting period for work permits that the law requires for migrants pursuing asylum cases.

On 1 September, the Department of Homeland Security began texting tens of thousands of migrants in New York City and around the country, alerting them that they could apply right away for work permits, prominently advertising something legal experts in the administration had long known. In a statement, homeland security officials promised “a government-wide effort to integrate newly arrived non-citizens into the American workforce”.

But it was not certain the improvised fix would succeed without creating new bureaucratic log jams, and ultimately it revealed the general dysfunction in the asylum maze so many migrants were trapped in.

Juan Carlos Bello was a migrant from Venezuela. On a sweltering summer day, he was expelled from a shelter in Brooklyn to make way for more recently arrived migrant families. He was stranded in the street, towing two suitcases containing all his possessions. He had been living in shelters, without a regular job, since he arrived 10 months earlier after wading across a river into Texas, his lodging and meals paid for by New York City.

He was grateful for the assistance, but like many migrants in the recent wave, Bello never wanted to live in a shelter, be unemployed or depend on any government. “I’m a working person,” he said. “I am used to living on what I produce.” In Caracas, before he had to flee from Venezuela’s leftist government, he had built a thriving business installing kitchens. He had skills, and all around in New York he saw construction jobs on offer.

But he was at least six months from obtaining a legal work permit and probably four years from a court decision on his asylum claim, given the legal and bureaucratic obstacles in the system. He felt diminished because he could not send money to sustain his wife and children who were stuck in Venezuela, including a young daughter with a heart condition. “There are no words to describe the anxiety,” Bello said.

As New York’s mayor has discovered, asylum is not a migrant labor program. It is specifically configured to discourage immigrants from presenting asylum claims just to obtain work permits.

In the early 1990s, fraudulent claims surged as immigrants, often prompted by unscrupulous attorneys, filed for asylum only to get the permits. With changes in 1995 and 1996, a 180-day waiting period was added before asylum seekers could be eligible for work authorization.

Migrants in the recent surge, whether or not they have legally compelling stories of persecution, are seeking asylum because, for most, that is the only possible route to legal status. Asylum seekers face a one-year deadline from the day they entered the United States to file a claim in court. Although New York is generous with legal services, competent attorneys who can prepare a persuasive claim are severely overworked. Migrants say they often put off filing until just before one year is up to maximize time to prepare their claim. In practice, most asylum seekers will wait at least 20 months before their work permit card arrives. Meanwhile, they cannot be employed legally.

With its new initiative, the Biden administration is avoiding the tortuous channel of asylum and shifting the focus to humanitarian parole. (In the immigration context, parole has to do with getting into the country, not getting out of prison.) Officials are taking advantage of existing rules that generally allow people who come in on a parole to apply for work permits right away, although the permit is valid only for the term of the parole.

Since October 2022, the administration created paroles to bring in up to 30,000 people each month from four countries in turmoil: Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela. This year, the administration has also been granting at least 1,000 paroles each day along the south-west border to people who come through a border station with an appointment via an app called CBP One.

By June, more than 308,000 people had entered the country through those two programs, according to official records. Paroles have been created for people from Afghanistan and Ukraine. But, according to Homeland Security officials, only a fraction of migrants with those paroles have applied for work permits.

There is an even larger group who may already be eligible for permits. Hundreds of thousands of migrants were released into the country with paroles during chaotic surges across the south-west border in 2022. Some were only granted for a few months, but many were paroled for a year or even two. Migrants who have border paroles that are still valid for some time can apply for permits, Homeland Security officials confirmed, a cohort that could include many thousands more people in New York and elsewhere.

For many, the news that they have long been eligible for work authorization will come too late – since their paroles are expiring soon or already have. Among them is Juan Carlos Bello, whose one-year parole will expire in late September.

Bello would seem to have a strong case for political asylum. After he joined the opposition to President Nicolás Maduro during an election in 2021, pro-government enforcers drove him out of his home town and burned down his house. But even for a man who endured seven days in the dark swamps of the Darién Gap between Colombia and Panama, it is taking all his stamina, savvy and prayer to keep moving forward in his legal odyssey.

He camped out temporarily at the Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd in Brooklyn, a gathering place for bewildered migrants looking for help to navigate the system. “Whatever honest work comes to me, I will do it,” Bello said. “No job has ever been a dishonor for me.”

Among the church’s new parishioners are Salomón Gutiérrez and Stella Ortiz, a couple from Colombia, both in their 50s. In their home country they opened supermarkets, a clothing shop and a soft drink distribution warehouse. Gutiérrez also drove petroleum tanker trucks. But roving criminal bands extorted their businesses and hounded their children, trying to recruit them. The couple fled, leaving everything behind.

The records of their border crossing in Texas in March 2022 were lost in the system. They received confirmation only this August that their asylum claim was properly filed with the courts, had received their asylum claim, starting the six-month work permit wait. Determined not to rely on government services, to earn a living they were forced into the underground economy. They purchased carts and went out to sell Mexican churros on the boardwalk in Coney Island.

Once they get their permits, Gutiérrez would like to get a truck driver’s license, to fill a critical shortage in the New York region. Ortiz thinks of training for work in home healthcare. Eventually they hope to start a new business. Ortiz just wants to follow the rules. “If I want to do things right,” she asks, “and work legally and pay my taxes and own my food and electric bill, why won’t you give me a work permit?”

Work permit processing has been clogged with backlogs for so long, it spawned its own resistance movement. The Asylum Seeker Advocacy Project, the membership organization formed to fight for faster and fairer treatment by federal agencies, has grown to more than 562,000 members nationwide.

A lawsuit the project helped bring in 2020 pushed US Citizenship and Immigration Services to comply with a requirement, written in law, that asylum seeker work permit applications filed after 150 days must be processed within 30 days. By this August, according to official data, 91% of asylum seekers’ first-time applications were decided within that time frame, a rare bright spot of efficiency in the bureaucracy.

Biden administration officials have touted those fast processing times. Concern about overburdening the chronically underfunded agency had made officials cautious about broadcasting the work permits attached to paroles that were immediately available.

But with the fog of information in migrant communities, officials have no good estimate of how many people will now come forward to apply. If there is a crush, backlogs and delays will build again. Conversely, people may need assistance to apply, which overstretched service providers will not be able to give. Homeland Security officials rankled Adams by insisting the city could do more to help with the permits. While asylum work permits are free, the government will charge $410 for a parole permit, a huge sum for many migrants. Also, the paroles have been challenged by Republicans in the courts, and officials worry that the whole program may be brought to a halt.

It is no secret that needy migrants are not waiting for permits to go out and work. They are helping alleviate labor shortages with off-the-books work in restaurants, and as delivery drivers, janitors and home healthcare workers.

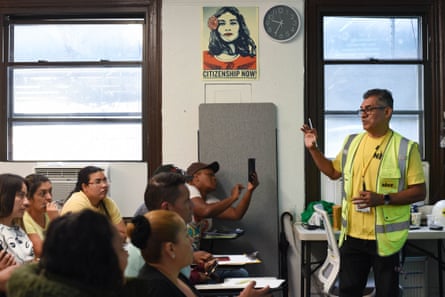

They are flocking to training classes, like the ones offered for future plumbers and electricians by New Immigrant Community Empowerment, an organization in Queens. Nilbia Coyote, the executive director, says the training is vital, whether or not the migrants will eventually get their work permits.

“We train them to know their rights, to demand protections, to have the safety education they need,” she said, “so they can go home to their families at the end of every day.”

This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a non-profit news organization covering the US criminal justice system."

No comments:

Post a Comment