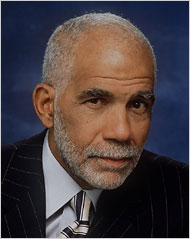

Ed Bradley, TV Correspondent, Dies at 65 - New York Times

Ed Bradley, TV Correspondent, Dies at 65

Ed Bradley, a fixture in American living rooms on Sunday nights for a quarter century as a correspondent on “60 Minutes” and one of the first black journalists prominently featured on network television, died yesterday in Manhattan. He was 65.

Mr. Bradley died at Mount Sinai Medical Center of complications from chronic lymphocytic leukemia, said Dr. Valentin Fuster, his cardiologist and the director of the Cardiovascular Institute at Mount Sinai. Mr. Bradley, who underwent quintuple bypass heart surgery in 2003, learned he had leukemia “many years ago,” Dr. Fuster said, but it had not posed a threat to his life until recently, when he was overtaken by an infection.

Even some close colleagues, including Mike Wallace, did not know that Mr. Bradley had leukemia or that his health had precipitously deteriorated over the last few weeks. His most recent segments on “60 Minutes” were on Oct. 15 (on the rape allegations against three Duke University lacrosse players, whom he interviewed) and on Oct. 29 (an investigation of an oil refinery explosion in Texas City, Tex.). On the day that that last segment was broadcast, he was admitted to Mount Sinai and remained there until his death.

Though Mr. Bradley had largely concealed his illness, he and his wife, Patricia Blanchet, had reached out in recent days to some of his closest friends — including Charlayne Hunter-Gault of National Public Radio (who traveled to his bedside from her home in South Africa) and the singer Jimmy Buffett (who rushed to New York to be with him following a concert in Hawaii).

Mr. Buffett said he told Mr. Bradley on Wednesday that “the Knicks and the Democrats won,” eliciting a smile from Mr. Bradley, who by that point could barely speak. Mr. Buffett and Ms. Hunter-Gault were part of a close-knit circle gathered at Mr. Bradley’s hospital room at the time of his death.

“This has been a long battle which he fought silently and courageously,” Ms. Hunter-Gault said. “He didn’t want people to know that this was a part of his struggle. He didn’t want people feeling sorry for him. And for a good part of his life, he managed it.”

To generations of television viewers, Mr. Bradley was a sober presence — albeit one with salt-and-pepper stubble and a stud in one ear — whose reporting for CBS across four decades ranged from the Vietnam War and Cambodian refugee crisis to the sexual abuse scandal in the Catholic Church and the Columbine High School shooting. His most prominent interviews over the years included those with Timothy McVeigh and the convicted killer (and author) Jack Henry Abbott, and with the performers Michael Jackson, Robin Williams and Lena Horne. He won 19 Emmy awards, according to CBS, including one for lifetime achievement in 2003.

In the three years since his bypass operation, Mr. Bradley had more than 60 segments broadcast on “60 Minutes” — more than any other correspondent. “And he kept track,” said Jeff Fager, the program’s executive producer.

But Mr. Bradley’s life off camera was often as rich and compelling as his life in the studio. Having begun his broadcast career as a disc jockey in Philadelphia, Mr. Bradley was an enormous fan of many forms of music — particularly jazz and gospel. He counted the musicians Wynton Marsalis, Aaron Neville and George Wein among his friends and made regular pilgrimages to the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. At his death, he was also the host of “Jazz at Lincoln Center Radio With Ed Bradley,” broadcast weekly on 240 public radio stations.

“I made the mistake once of letting him get onstage with my band, and he never stopped doing it,” said Mr. Buffett, who was introduced to Mr. Bradley 30 years ago in Key West, Fla., by a mutual friend, Hunter S. Thompson.

Mr. Bradley had many nicknames throughout his life, including Big Daddy, when he played defensive end and offensive tackle in the 1960s at Cheyney State College (now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania); but his favorite, Ms. Hunter-Gault and Mr. Buffett said, was Teddy Badly, which Mr. Buffett bestowed on him onstage the first time Mr. Bradley played tambourine at his side.

“Everybody in my opinion needs a little Mardi Gras in their life,” Mr. Buffett said, “and he liked to have a little more than the average person on occasion.”

“He was such a great journalist,” Mr. Buffett added, “but he still knew how to have a good time.”

Edward Rudolph Bradley Jr. was born June 22, 1941, in Philadelphia. His father was a businessman and his mother a homemaker. After his parents divorced, he spent summers with his father at his home in Detroit, said Marie Dutton Brown, a literary agent and Philadelphia native.

Ms. Dutton Brown said she met Mr. Bradley in the mid-1960s, after he graduated from Cheyney State with a degree in education, when both worked for the Philadelphia schools. Mr. Bradley, she said, taught elementary school.

At the time, she said, his dream was to attend the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. But on the strength of his work in his other job at the time — at WDAS radio, where he was a news reporter and host of a jazz show — he was hired as a reporter at WCBS radio in New York. “And that was that,” Ms. Dutton Brown said.

In 1971, after four years at WCBS, he joined CBS News, as a stringer in its Paris bureau. The next year, he was reassigned to the network’s Saigon bureau, where he stayed until 1974, when he moved to its Washington office. Mr. Bradley, who was wounded on assignment in Cambodia, had become a full-fledged correspondent while in Southeast Asia. In 1975, he volunteered to return to the region to cover the fall of Saigon.

His reporting on Cambodian refugees, as broadcast on the “CBS Evening News With Walter Cronkite” and “CBS News Sunday Morning,” won a George Polk Award. After covering Jimmy Carter’s presidential campaign, he covered the Carter White House from 1976 to 1978. He was also anchor of the “CBS Sunday Night News” from 1976 to 1981.

It was in 1981 that Don Hewitt, the founding executive producer of “60 Minutes,” hired Mr. Bradley for the program, the most prestigious (and arguably the most competitive) news magazine on television.

And yet, despite having to jockey for airtime with heavyweights like Mr. Wallace and Morley Safer, Mr. Bradley stood out — in no small measure because of the competence and decency he conveyed, said Mr. Fager, a longtime producer on the program who succeeded Mr. Hewitt last year.

“Not only was he just a natural broadcaster and storyteller, but he was filled with integrity and credibility, in the way Cronkite was as an anchorman,” Mr. Fager said yesterday. “He had no pretensions. He was a remarkable, likeable, wonderful man you just wanted to be around.”

He also had a wicked sense of humor. At one point, Mr. Fager said, Mr. Bradley tried to convince Mr. Hewitt that he wished to change his name to Shahib Shahab, and thus the opening of the “60 Minutes” broadcast to: “I’m Mike Wallace. I’m Morley Safer. I’m Shahib Shahab.”

“He let the gag run for quite some time,” Mr. Fager said. “Don was quite concerned.”

Mr. Bradley, who had no children, is survived by Ms. Blanchet, whom he married two years ago at his home in Aspen, Colo., said Ms. Hunter-Gault. His two previous marriages, to Diane Jefferson and Priscilla Coolidge, ended in divorce, Ms. Hunter-Gault said.

For Ms. Hunter-Gault, who left The New York Times for the “MacNeil/Lehrer News Hour” on PBS in 1978, Mr. Bradley was more than just someone who helped clear an early path to national television for herself and other black journalists — a distinction he shared with, among others, Max Robinson and Lem Tucker.

“I think people might want to characterize him as a trailblazer for black journalists,” she said yesterday, by cellphone from outside Mr. Bradley’s hospital room just after his death. “I think he’d be proud of that. But I think Ed was a trailblazer for good journalism. Period.”

In the weeks before his final hospitalization, Mr. Bradley had been scrambling to finish the Duke report in particular, while fending off what would become the early stages of pneumonia.

“He just kept hitting the road,” Ms. Hunter-Gault said. “Every time I talked to him, he was tired. I’d say, ‘Why don’t you go home and rest?’ He’d say, ‘I just want to get this piece done.’ ”

“He was proud of what he did,” she said. “But he never allowed that pride to turn him into a star in his own head.”

“In his own head,” she added, “he was always Teddy.”

No comments:

Post a Comment